1906 spring game? Yes and no

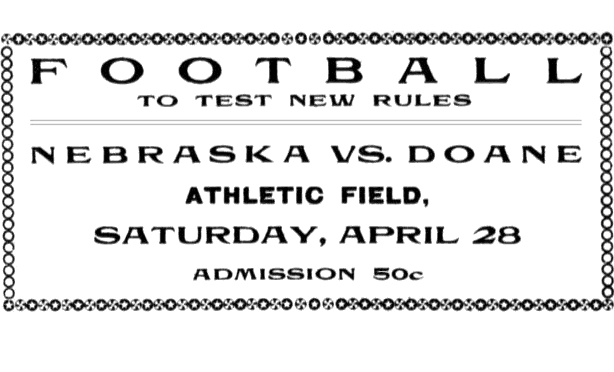

There’s no denying that Doane and Nebraska tangled on the gridiron in Lincoln on April 28, 1906, but this game had a purpose unlike any of the others we now call spring games.

A sea change in football was just getting under way. The game had come under siege because of frequent deaths and gruesome injuries. In late 1905, Theodore Roosevelt summoned the game’s powers that be to the White House. A football enthusiast himself, Roosevelt told them their sport must change in order to survive.

Roosevelt

Prof. Lees

Nebraska’s players included at least one departing senior from 1905, lineman Charles Cotton.

The president’s persuasion worked, and sweeping reforms were formally adopted at the end of March 1906. The dangerous flying wedge formation was now banned. The neutral zone was created. Roughness penalties were stiffened. Forward passes were now legal. The distance to gain in three downs was now 10 yards, double what it had been.

Those were just some of the rule changes. In theory, they would transform football into a less brutal and more wide-open game. But would they really? It was a topic of hot debate.

Enter the Nebraska and Doane football players, guinea pigs for the reforms.

In early April, plans were announced for an exhibition game in Lincoln to give the freshly minted rules a public test run. There’s a good chance the idea was hatched by Nebraska professor James T. Lees, chairman of the university’s athletic board and a member of the intercollegiate committee that drafted the rules.

This came at an awkward time for the Cornhuskers, for they had no coach. Walter “Bummy” Booth and his sole assistant, John Westover, had resigned in January, and their replacements — Amos Foster and T.M. Stuart — wouldn’t arrive until September. Ten days before kickoff, the Huskers began practicing for the game on their own. Over in the next county, Doane’s team also was hard at work.

As the game drew near, it attracted more than just local interest. A Lincoln Star preview said representatives of “the leading colleges and universities of the west will be present to witness it.”

What they witnessed wasn’t pretty. Exciting plays and sustained drives were few on that Saturday afternoon, and poor weather made for a muddy field and disappointing attendance. If you enjoyed seeing two plays and a punt, followed by two more plays and another punt, then this game was for you.

Being so new, forward passes were a non-factor. They weren’t exactly encouraged under the new rules, as an incompletion carried a 15-yard penalty or was treated as a turnover, depending on whether the ball was touched before hitting the ground.

The only touchdown in the 6-0 contest came in the second half when Doane fumbled during a punt return and Nebraska’s Ernest Little recovered the ball behind the goal line.

Referee F.D. Cornell opined afterward that the changes had given the defense too great an advantage. Nebraska lineman Charles Cotton agreed, saying, “You can’t make ten yards in three downs.” Husker captain John Glenn Mason predicted football would become “a great disappointment.” Professor Lees also wasn’t convinced the rules committee had gotten it right.

The reformed version of football obviously survived its choppy introduction at Nebraska, Yale and elsewhere. In 1912 came more changes, including end zones and six-point touchdowns, plus one revision that vindicated some of those 1906 naysayers: the addition of a fourth down.

* * *

EPILOGUE: Let the hair-splitting begin. Was this a true spring game, or was it a game that happened to be in the spring?

While noteworthy for its own reasons, this one was clearly an outlier. It was not an upshot of normal spring drills, which didn’t amount to much during the first decade after their 1901 introduction. Nor was it an intra-squad game (though neither were the midcentury Varsity-Alumni contests). It was more of a lab experiment than an effort to make the team better.

Aside from this 1906 game, no mention of actual scrimmaging in the spring at Nebraska can be found in newspaper archives before 1915. That’s the year coach Jumbo Stiehm was preparing his team for a spring game that didn’t pan out. After that, seven more years would pass before the 1922 Cornhuskers played what we will continue to regard as the program’s first spring game.