Anatomy of an Era: Tom Osborne, Part 1

Excerpted from Chapter 47, No Place Like Nebraska: Anatomy of an Era, Vol. 1 by Paul Koch

In addition to all the engineering and business courses, I also studied four years of psychology and abnormal psychology ….I’m not being facetious when I say that these were probably the most valuable courses of my college career.

-Lee Iacocca, Iacocca: An Autobiography, with William Novak

When histories are written, men are most often defined by their successes, their failures, and to a lesser extent, the choices made in arriving at those destinations. Such is the personage of Thomas William Osborne. A man of action, words, and deep introspection, he’s been a moral compass, a study in leadership styles, a Christian model, and a surrogate father for over a generation of Nebraskans.

In my mind, his defining moment will forever be his “Forget the polls, we’re going for the win” two-point conversion call on January 2nd, 1984. What I find most peculiar and providential about that fateful night is the quirky coincidence of his name’s monogram: T.W.O., as if he was destined for that precariously illuminating situation long before history had run its course.

A man described by some outsiders as stoic, insular, overly private, ethically challenged and even morally bankrupt on one occasion, I and many, many other individuals know reality to be just the opposite, as experience and interaction have revealed a bedrock strength of meekness, humility and intellect. His inspiring aura often makes you want to gather together and accomplish something larger than you could merely do by yourself, to strive to be a better man at everything in life. To quote former trainer Jack Nickolite, “If I were a quarter the man that he is, I’d be twice the man that I am.”

Let that sink in for a second, then listen in on this brief conversation with someone I’ll forever know as ‘Coach,’ as we pull the curtain back on the man, his mindset and some rationale for his methods.

Notable quote #1:

“A lot of times if you look behind the behavior you’ll begin to understand more. And I think, as a result, many times we got maximum effort out of players because they felt that they were important, that we cared about them as people. We were certainly interested in winning football games, but were even more concerned with their general welfare.”

Tom Osborne

Question: Good morning Coach. I appreciate your making some time for me. If you don’t mind, I have a few questions.

Tom Osborne: That would be fine.

Q: Well, for starters I re-read your book ‘Faith in the Game’ last night, and it made me curious… how did your Doctorate in Educational Psychology help you as a football coach?

TO: Well, I think it helped me to realize that sometimes behavior wasn’t always caused by what it appeared to be on the surface. Sometimes people say, “He’s just lazy” or “This person is trying to show their independence” or “This person is just stubborn,” and you realize that a lot of people don’t really want to behave in ways that are destructive or obstructive. And you realize that usually behavior is caused by a reason. And that maybe caused me to listen a little bit more and fly off the handle less; instead of telling people what to do, trying to listen a little bit more for what is behind the behavior.

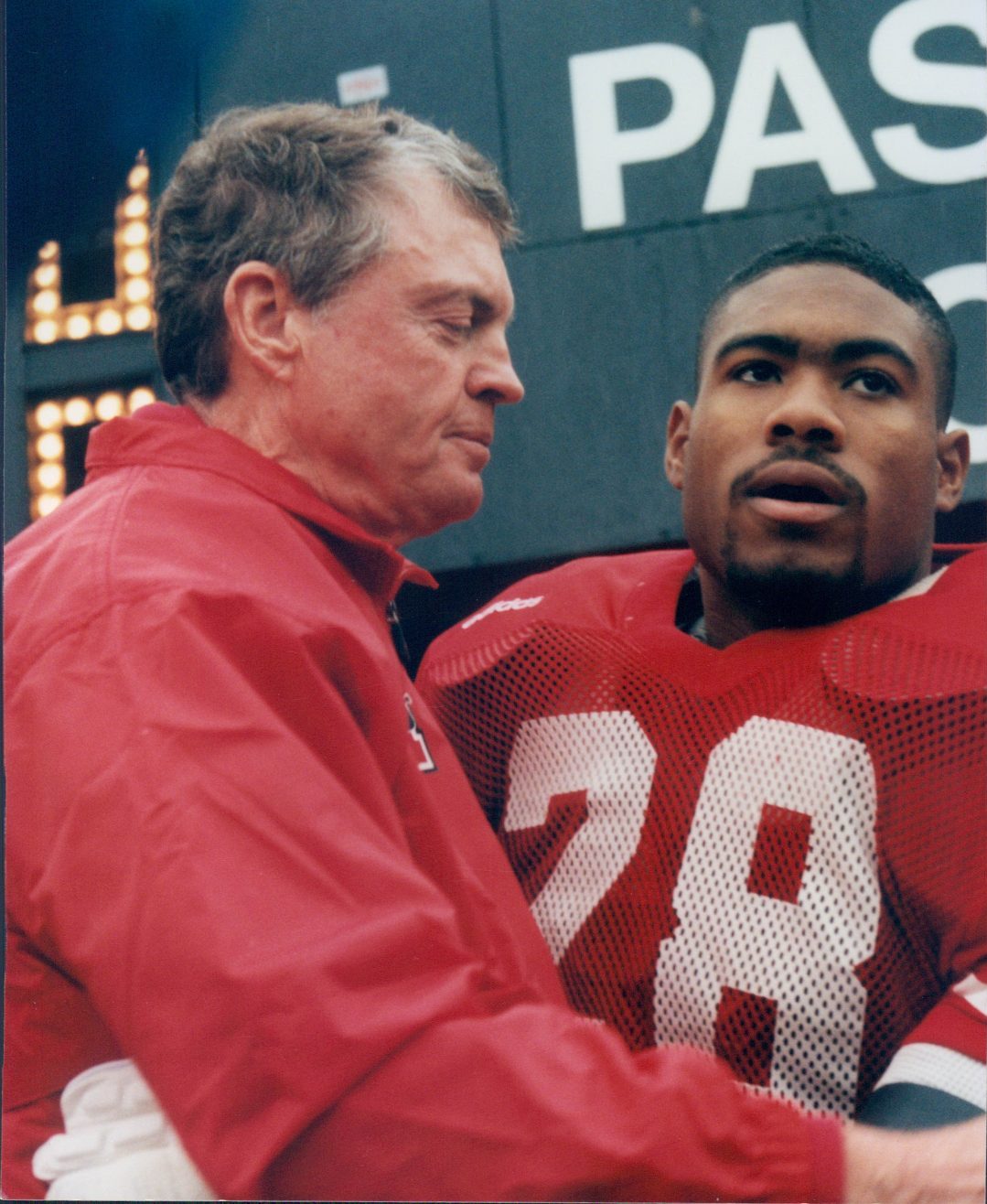

A Senior Day embrace with Jamel Williams

That didn’t mean I was trying to psychoanalyze every player; I wasn’t doing that. But I just realized that maybe a player was playing poorly, but if you sat down and listened to him you found out his grandmother was dying, for instance, and his grandmother was the one who raised him. And so a lot of times if you look behind the behavior you’ll begin to understand more. And I think, as a result, many times we got maximum effort out of players because they felt that they were important, that we cared about them as people. We were certainly interested in winning football games, but were even more concerned with their general welfare.

Q: It always seemed like you were a very good listener. Was that something you had to work on?

TO: Well, to some degree. But as I said, I think that realizing that if you listen you can oftentimes understand people better. And one of the greatest needs people have is to feel understood. Even though you may not be able to fix the problem, if a player felt that I at least tried to understand him, understood where he was coming from, it made a difference. It seemed to fire them up to play to the best of their ability.

Q: Did you have any coaching role models or people you wanted to emulate when you first got into the business?

TO: I think the person in the coaching profession who’s had the most important influence on me was someone I never really saw coach in person: it was John Wooden.

But I read a lot of what he wrote, talked to him on the phone a few times and have met him a couple of times, and I was always quite interested in his approach to coaching. I thought, philosophically, we were fairly similarly aligned. One thing that John emphasized is ‘the process,’ how you do things was more important than the final outcome. And if you did things well enough and often enough over a long enough time period then hopefully the outcome would be good.

A word with the packed Devaney Center crowd post-Miami victory. (Unknown/Uncredited)

But he never talked about winning, never focused on winning: “Focus on how you put your socks on, how you bend your knees when you shoot a free throw, how you dribble, the techniques of passing,” the process that you go through every day to get better.

Q: You seemed to have a lot in common with a lot of basketball coaches. Is there any rhyme or reason to that? Are you an inherent basketball fan?

TO: No, I played basketball. I played basketball in high school and college, but football was my first love. I just happened to find a guy like John Wooden was probably the person in coaching who seemed to align philosophically with me better than anybody else. Although I certainly have been a close friend and admirer of Bobby Bowden, Bo Schembechler. I saw things in Bo that I liked, and Joe Paterno to some degree, but John Wooden would be the one who had the most influence.

Q: Was there one great, important lesson you learned or experienced as a player that you were able to bring into your coaching? Which made you a better coach?

TO: Oh, I think maybe when I went to the National Football League. I was an 18th-round draft pick, as I recall. At that time there were thirty rounds. There were thirty rookies that came in plus another 20 or 30 free agents. And I think there were 36 spots on the team at that time, and there were 36 veterans. So the odds of my hanging around were just about zero, coming from a small college.

But I found that perseverance, you know, just hanging in there and going to practice the next day, working hard, I saw guys eliminate themselves. The #1 draft pick got homesick and got on a bus one night and left camp. One other guy dropped out. Somebody would get hurt and you realized that perseverance is really critical to any kind of endeavor.

Q: In your book you said that he actually asked you for a ride to the bus station. You were more than willing to oblige him, eh? (laughs)

TO: Yeah, I drove him down there. He was a guy I knew. He was a friend. He just had really made up his mind he was leaving so I drove him down.

Q: I have to tell you, Coach, in talking to all of these former players they’ve spoken about the Unity Council and the empowerment it brought, but they also infer or mention the love that existed in the program. Love and caring for one another was absolutely pervasive. Any comment on that?

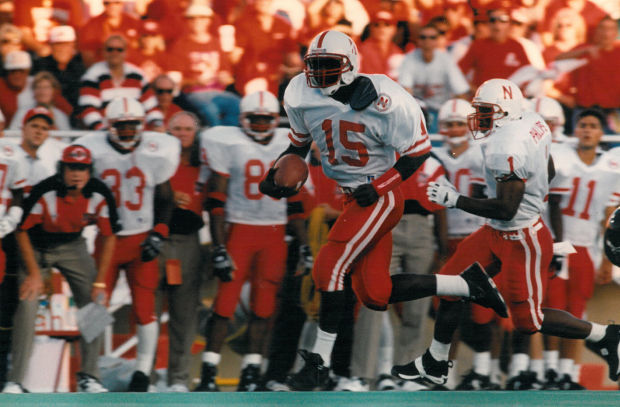

The Bugeater Express (Lincoln Journal Star)

TO: Well, we certainly tried to put players first and let them know that whether they were a first-team player or fourth-team player, that we cared about them as individuals. And I guess you show that in various ways. I tried to spend some time down in the weight room every day after practice and I talked to five or six guys maybe for three or four minutes each. And by the end of the season I’d talked to most everybody several times and knew a little bit about their family, what was going on academically, wouldn’t let them play if they didn’t perform academically, let them know their education was placed above football, that their health was important.

Obviously, we never tried to play a player that the medical staff said wasn’t ready to play, and so I think by showing concern in various ways by listening to them and getting to know them personally, that they felt cared for. And I think that was important.

And I think that when the coaches care about you that you’re a little more apt to care about the program, about other players. And so I think that overall the chemistry really came together very well.

Both volumes available on Amazon.com

Q: You probably know it already, but a wonderful brotherhood still remains from those days in the ’80’s and ’90’s. And one thing that seems to shock so many of the players was your ability to remember so many people’s names, their family members’ names. I have to know, how do you do it?

TO: Well, of course, when you go out to recruit them you meet all these players’ families. And I guess what’s important to you… you remember what’s important to you. It was always important to me.

And I think that, of course, spending time either at the training table or the weight room talking to them personally, you’d get a little better chance to pick up on their personal life and their family and how things were going. And that was always important.

Q: I believe you said that you came to knowledge of a saving faith in Christ at 20 years of age, is that right?

TO: Yeah. Nineteen or twenty, uh huh.

Q: How did that come about? Can you tell me?

TO: Well, I had grown up in a Christian home and had always gone to church and Sunday School, and so it wasn’t that I was without faith. But I guess that most people, as they are growing up their faith tends to be second-hand faith -the faith of your parents- and at some point you have to decide, really, what your faith is.

So I went to a Fellowship of Christian Athletes conference out in Estes Park, Colorado in 1957, and at that point I guess I heard Christianity expressed and explained in a little different way than what I’d heard in church, and then I saw the vitality and the virility to Christianity, the realization that this was something that was very demanding, that might require you to even sacrifice your life if you’re going to be faithful. And I guess I heard it expressed and articulated by people I could relate to, other athletes, a number of professional athletes. There were a number of players from Oklahoma and LSU and other schools that I could admire. So anyways, it was during that week sometime that I made a spiritual commitment that I never turned away from.

Q: You talk about a demanding faith. Going throughout your personal history it seems you’ve enjoyed taking on very demanding things, that you are very competitive. What was the genesis of that competitive spirit?

TO: Oh, I really don’t know. I’ve never seen myself as someone who’s terribly competitive, but I guess anyone who’s in coaching probably has a competitive streak. And of course, I was involved in athletics from an early age and I played ’em all: football, baseball, basketball, and track. So I’ve been in a lot of competitive situations. But I can’t tell you exactly where that comes from; it’s something that I’ve always enjoyed, the competition.

Never stop making a difference (Kathy Koch)

Q: Some people love competing to prove something to themselves, sometimes to prove something to others, or maybe a combination of the two. What drove you?

TO: I don’t know. I know that my Dad being overseas during World War Two and returned when I was about 9 or 10 years old, I knew that athletics was important to him and wanted to get to know him better and gain his approval, so I’m sure some of my athletic competitive nature in competition may have had to do somewhat with my Dad.

Still, it’s something that you either have it or you don’t. Some kids just naturally like to compete and challenge themselves and some people don’t. I always found that it’s something that was appealing to me, to test myself in competition.

Q: You said football was your first love. What was it about the game of football that made you really cling to it?

Tom’s final locker room victory celebration (Dave Finn)

TO: Well, I enjoyed the contact. Some people didn’t like scrimmages; I always liked scrimmages, I always liked games. And even though I was not built like many football players -I guess I was relatively slender- but I still liked the contact of it. So I just enjoyed the game. And as time went on I began to enjoy the strategy of it more, and I believe I even called my own plays in high school and most of my years in college I called the plays.

To be continued….

Copyright @ 2013 Thermopylae Press. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credits : Unknown Original Sources/Updates Welcomed