Anatomy of an Era: Sonya Varnell, Part 1

Excerpted from Chapter 87, No Place Like Nebraska: Anatomy of an Era, Vol. 2 by Paul Koch

“You(‘re) dealing with so many issues,” Osborne said. ”You have more than 100 young guys that have a lot of energy and come from diverse backgrounds and you do the best you can to make sure they are good students, good athletes and good people… So that was probably the most difficult and yet it was the most enjoyable.”

-Coaching Still a Part of Nebraska’s Tom Osborne, Matt Murschel, Orlando Sentinel, May 22, 2011

This conversation was conducted with a sparkplug hailing from rural Mississippi by the name of Sonya Varnell. Sonya was a Husker recruit of a different sort and a hard sell, as you’ll soon learn.

A former trackster from Ole Miss, the quartet of Coach Osborne, Roger Grooters, Dennis Leblanc and Keith Zimmer made a dash to bring in someone of color, a soul-sister who could further empathize, acclimatize, actualize and help capitalize on the budding talent being developed on the field and in the classroom. If Nebraska Football were a human body, she was the connective tissue always stabilizing and stretching and holding things together behind the facade. But only to a point, as you’ll see.

Sonya was a building block in the pyramid of success that escalated Husker Football to near invulnerability. Not without her own personal struggles in a sometimes cold, seemingly foreign land, her steppingstone experience lent itself to character development and the genesis of better informed perspectives. Filling in the missing gaps as only she could at that time, what Sonya brought to the table created better bonds among the athletes and a well-lit footpath where previously darkness had slowed team progress. Let’s listen in on Miss Sonya Varnell: one tough, young mother in Nebraska’s halls of academia during that great 60 & 3 era.

Notable quote #1:

“The recruiting weekends when we’d have the tours and all the demonstrations and everything… the African-American parents and the kids in the group, they would always pull me to the side and ask, ‘Okay, what is it really like up here?’ ”

Sonya Varnell

Question: Hello, Sonya, great to talk to you once more! So let me start by asking, where were you born and raised?

Sonya Varnell: I was born in Mississippi and I was raised in the small town of Brandon, Mississippi.

Q: When you say ‘small town’, what was the population?

SV: Oh my gosh, very small. In fact, maybe 5,000, if that. I don’t think I ever knew the population when I was growing up there. It was very ‘country’ and we had one traffic light. Yeah, I grew up on a pig farm.

Q: You went to Ole Miss and ran rack, right?

SV: Yes, I did. I graduated in ’89.

Q: What did you do after graduating?

SV: I stayed there at Ole Miss and I was a Graduate Assistant Track Coach and got my Masters in Public Administration.

Q: So now you’re an Associate AD at the University of Southern Mississippi?

SV: I’m the Senior Associate AD for Olympic Sports.

Q: I’m sure that keeps you busy.

SV: Oh yeah, keeps me hopping.

Q: How did you end up in Lincoln, Nebraska?

SV: Do you remember Roger Grooters? Roger Grooters in Academics? I guess in his mind there were some issues with the African-American athletes there. Number one, there weren’t that many of them, and number two, there weren’t that many African-American students there, period. So I think that he wanted to start something to try to help the athletes, be it football or basketball or whatever, to somehow assimilate into the population there in Lincoln. When I was working at the Southeastern Conference we had done some work with the Anti-Defamation League and somebody told him about it. So he gave me a call.

He actually called my boss -and my boss told him to talk to me because I’d put the thing together- and Roger told me he was creating a new position there at the University, and the person could basically outline the whole job description and come in line with what he was wanting to do. And I wasn’t real interested, because I’d never really been past the Mississippi River (laughs) and knew nothing about Nebraska other than that it was cold. And I’m a Southern girl, so I would not be used to all that stuff, but I listened to what he had to say on the phone and told him I’d think about it.

And I guess a week or so went by and Roger was at a conference I was attending, and someone introduced us and I was able to put a name with a face. And he said, “Why don’t you come up? Come up to Nebraska and check it out and you can tell me what you think.” The rest, as they say, is history. And you know what? The two days I was there in Lincoln there was a snowstorm and I was terrified, and I was slipping all over the ice and stuff. And Keith Zimmer, who was driving me around, said, “Oh, this is unusual. This typically never happens.” And I was like, ‘Right!’ (laughs) He was, “This is very unusual for us to be having a snowstorm at this time of year. This is very out of the ordinary” -because it was something like March, if I recall- “Don’t let the bad weather scare you.” (laughs)

Roger Grooters

Q: So you flew in, right?

SV: Yeah, I’m trying to remember if I flew into Omaha or Lincoln. I think it was Lincoln.

Q: What year was this?

SV: 1993. I think it was during the school week. Keith was giving the tour, and we went to Dennis Leblanc’s house for dinner. I know my original thoughts were, ‘Oh, my God… it’s cold here. It’s freezing!’ I did have a little jacket with me, but it was nothing. I remember I couldn’t wait to get into the buildings, and even then I was cold. I was freezing. They were giving me the tour of the Hewitt Center and the training table, and I was very impressed with it, was impressed with Memorial Stadium. And they took me over to the Bob Devaney Sports Center and the track and all that stuff over there. It was really nice.

Q: Do you recall meeting any of the athletes or getting a take on what you would have hoped to accomplish?

SV: I was introduced to some athletes of the different sports who were there eating at the training table. I was really impressed with the staff at the dining facility, because they were really nice to me. Even my time there, they really took care of me. I was very impressed. There were kids everywhere.

Q: So despite freezing your hind-end off, you still made the decision to come to Nebraska. What was it that got you over the hump?

SV: I think it was a good opportunity, because Roger told me I could write the job description -and he had an idea- but he was going to leave it up to the person who filled the position. And most of the time you take a job that’s already been developed -it’s already been set as far as what your responsibilities are and what you’re supposed to do- and this was my opportunity to start something new. I was very excited about the challenge of it.

Q: Wow! Blazing a trail, huh? What was your title?

SV: I want to say ‘Coordinator of Multi-Cultural Programs for Athletics’ or something close to that.

Q: In the process of creating that plan, was there a major hurdle you had to overcome? Was there something drastically lacking at the University of Nebraska that you had to conquer?

SV: You might say, “multi-cultural”, but there was no “multi-cultural” there. Not that that was bad, but everything was “white.” (laughs) You didn’t have a large Hispanic population: maybe less than one percent. The African-American population was even smaller: I don’t think it was even one percent. And the Asian population was almost nonexistent. Normally when you want to make kids feel like they are a part of something you want to have people that somewhat look like them to try to break the ice and get them involved in the community in different areas, and that wasn’t there.

Q: So, knowing Nebraska athletics like I do -or did, anyway- if you were not a Caucasian on campus you were pretty much a lock to be a member of the basketball, football, or track teams, right?

SV: True. If you were African-American, for example, you more than likely were a member of the football team, basketball or the track team. The softball team maybe had one, I don’t think gymnastics had any. Women’s swimming and diving didn’t have any. The wrestling team had a couple.

Q: From the black perspective of an athlete new to campus, what was the most beneficial way you assisted them, the greatest way you met a need? Did they feel as if they were initially on the outskirts? Was there a true need to assimilate?

SV: That’s not an easy question to answer. And I have to say, once I was on the job there for a week or two, Roger Grooters took a job at Michigan State or something like that. Then Dennis Leblanc got the job and one of the things he asked me once was, “Why is it that the black athletes always segregate themselves?” -like at the training table, you know how they always used to sit back there in that corner- and I told him that I didn’t see it as segregation because all the white kids come in and they sit together. And he said, “Well, I never thought about it like that.“ And I said, ‘They just stick out because they’re a different color.’ I told him that it was a “comfort zone” for them after they had been going to class and doing all this stuff on campus, because they normally don’t see another person who looks like them until they come over here to the athletic department. ‘It’s a comfort zone where they can sit down with each other and talk the way they want to talk, not feel like they’re being scrutinized or something like that. Even if they’re speaking ebonics or they’re English is broken down, there isn’t anyone who’s going to say anything about it.’

Available on Amazon.com

Q: Interesting: the term “comfort zone.” And you -yourself- arriving in Nebraska… I’m sure you had some experiences dealing with all the homogeneity, or lack thereof?

SV: I’m not sure if I ever told you this, but I remember the first time I was in Shopko -and I was in the aisle where they have the shampoo and stuff like that- and I was looking and looking for a specific product for my hair and I didn’t seem to see what I was looking for. I figured maybe I was in the wrong aisle, so I went to talk to a lady who worked there and said, ‘I’m sorry, but can you tell me where your African-American hair care products are?’ And she said, “Give me one minute.” So I waited there a few minutes and another person come up to me, and he’s the Manager. And I say to myself, ‘Why is the Manager coming to talk to me?’ So he says “Can I help you?” I said, ‘Yes, I’m looking for the African-American hair care products?’ And he said, “Oh, I’m sooooo sorry. We don’t have any. But our store in Omaha carries a lot.”

That’s what he said. I mean, I’m in America and I’d never before -in my entire life- can’t get what I want for my hair or my skin or whatever. And I said, ‘Are you kidding me?’ And he said, “No, I am so sorry.” And I said, ‘You mean you have nothing? No? Nada?’ And he said, “I’m sorry, our population just isn’t large enough to stock those products.” I couldn’t believe it!

Q: (laughing) I’m sorry, Sonya, but I’m just laughing at the image of you standing there in shock in the store’s aisle, jaw agape…

SV: Yeah, I just couldn’t believe it. I was in total shock. Up until that point most of my life had been in the South where I could go to any grocery store to get what I needed. I couldn’t believe this. I felt like I was in a foreign country and I was speaking a language that he could not understand. ’You have nothing?!’ “No ma’am, but we have a lot of that product in our stores in Omaha.” And I was, ‘Well, I don’t live in Omaha, I live here in Lincoln.’

Q: So what did you end up doing?

SV: Well, I told Dennis and he was kind of embarrassed about it. And he was shocked. We were both shocked. Because that was something that he never had to think about.

Dennis Leblanc

Q: I’m sure Dennis never before went shopping for black hair care products…(laughing)

SV: He’d never had to deal with that. He was, “Oh, my God. I never thought about that. What about K-Mart?” And it was the same thing with K-Mart. I know there’s black people that lived here, and they had nothing? And Dennis’s wife, she was selling Mary Kay or Avon and she lent me some little makeup for darker skin and lipstick. They didn’t even have the darker shades for black people in the makeup. I was like, ‘Am I gonna have to ship some things in from the South?’

And then I met Dr. Keith Parker, who was professor over there in Sociology, and he told me there were African-American hair care products over at a place called Sally’s, a beauty store where hairstylists and barbers go to get their supplies. So I went over there and, voila, they had everything I needed.

Q: You didn’t have to make a road trip to Omaha?

SV: No, I didn’t have to do the road trip. It was very funny, though I couldn’t believe it. I called my sorority sisters and everybody, telling them about it. I was like, ‘What have I gotten myself into?’ (laughs)

Q: (laughs) This may be a touchy subject, but did you ever encounter any bigotry or racism of a harder-edged, overt kind while in Nebraska?

SV: No, I did not. I found the people of Lincoln to be very friendly and earthen. My daughter did (and it’s unfortunate that children can be so mean), but for me it was not. When we first got there my daughter was at an after-school program at the YMCA and some boy told her that she “looked like a turd.” And of course, when I went to pick her up that day she told me what happened. And of course, I was upset. And they said they spoke with the young boy, but that didn’t help my kid.

Q: I understand. So, when a new athlete arrived you probably felt inclined to spare them the ‘hair care tragedy’ that you experienced?

SV: Oh, definitely. And especially if there was a female. And you know, there’s a difference between the male athletes who are black and the female athletes, because you know guys… they can deal with whatever. And you know the recruiting weekends, when we’d have the tours and all the demonstrations and everything? The African-American parents and the kids in the group, they would always pull me to the side and ask, “Okay, what is it really like up here?” (laughs)

Q: What would your response typically be?

SV: Well, I told them if they wanted their young man or young woman to get a degree, this is the place to be, because the University of Nebraska is graduating African-American kids -male and female- at a higher rate than the rest of the country. Now, if they aren’t used to an all-white environment it’s going to be a culture shock, because there are not a lot of African-American students here. So your student -your child- will be doing some interracial dating more than likely. I don’t know if that’s a problem for them, but I can see around here that I don’t think it is.

Especially for the male athletes there, it’s great. Because the black women want them, the white women want them, the Asian and whatever else there might be. Now, the African-American females on the other hand, I just didn’t see a lot of interracial dating with them. So normally, if they’re dating somebody it’s normally a black guy. Why? I don’t know. But I venture to say the white males who are there don’t have to date outside their race because there are a lot of white women to date there.

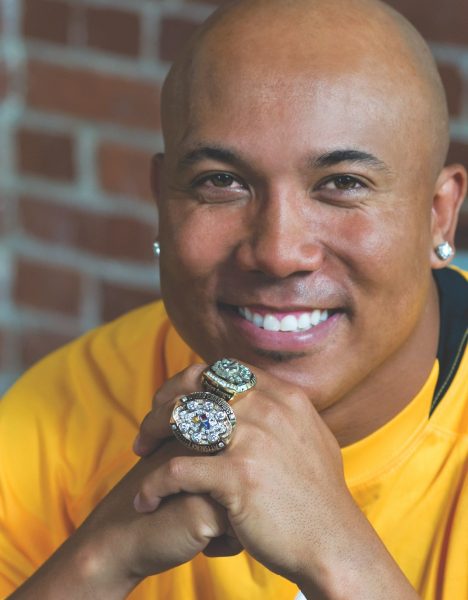

And one young man I remember: Hines Ward. Do you remember Hines Ward? He came on a recruiting trip to Nebraska but ended up going to Georgia. Hines had pulled me aside -and he was a military kid; I believe his father was black and his mother was, if I remember, Filipino, maybe Thai- and he asked me what it was like here for black people, for Asian people? I told him, I said, ‘Well, I won’t lie to you. It’s going to take a little adjustment. The people aren’t bad people. Even though their skin color might be a little different they’ll treat you fairly.’

Hines Ward

And he said, “Well, I’m really thinking about not coming to Nebraska.” And I said, ‘Why? Because of the color issue?’ And he said, “No, it’s because I don’t think I’ll be able to play here.” I said, ‘Why do you say that?’ And he said, “Well, Tommie Frazier is the man. And he’s only a sophomore, (laughs) and I don’t see that changing anytime soon, because he’s good.” And I said, ‘Well, you don’t know. Maybe you’ll come and beat him.’ And he said, “I don’t know.” He was really funny on his recruiting trip. I bet you he doesn’t even remember talking to me on his recruiting trip, but I remember him. He wasn’t a big superstar or anything, but I remember him. He was like most Southern guys: very talkative and very excited to be there and, of course, complaining about the cold. And I said, ‘What you’ve got to remember is, you’re not outside all the time. And even when you’re practicing you go inside.’

Q: He didn’t want to buy a winter coat is what it came down to? (laughing)

SV: Exactly. And then he ends up playing for Pittsburgh, where it’s really cold. I thought that was funny when he went to the Steelers’ team.

Q: (laughs) Interesting. Your last year there at Nebraska?

SV: It was 1997.

Q: So you were there from ’93 to ‘97. Those were some great years, Sonya. If you could give me a general description of the culture, the tenor of the time, could you reflect on it?

SV: All the confidence, especially around the football program, we just thought our team was unbeatable. Even though there was a slight edge on the other teams’ behalf and we were the underdog, it was like, “Whatever.” (laughs) You could call it arrogance, but it was like, “We’re not losing.” And even when we did lose it was a shock. When we won the back-to-back national championships were we undefeated? Yeah, those young men did so well and it was so exciting, sometimes to a point where some young men, they got beside themselves. What I mean by that is, they felt like they could do and say whatever, because they were winning. And so, how dare you tell them to study and stop talking, or they have to go to this program or whatever. The majority of them followed the rules and did what was asked of them, but you had a few. I don’t want to mention any names because you are recording, (laughs) but you had one guy who always came in for study hours and signed in, but then he would leave right away. Then when you called him on it he’d try to intimidate you and say, “I was there, you saw me. You saw me.” ‘Yeah, I saw you… then you left. You were there. I saw you walk in the whole place and walk around the place. Plus, you’re so big and the Hewitt Center is not that large, so there’s no way you could have been hiding from me.’

Q: Just like any child, they’re constantly testing boundaries, huh?

SV: Yeah. And Lawrence Phillips comes to mind, because he –he wasn’t a bad kid. I don’t know if he knew how old I was, but I guess he used to say stuff about me. Like him and some other guys would be laughing when I’d walk by. So he must have been saying something about me, right? Well, one time Lawrence handed me a note. And I looked at the note, and it had some numbers on there. And I said, ‘What’s this?’ He said, “That’s my number. When you want to get with a real man, call me.”

And of course, everybody fell down laughing. And I looked at him and I said, ‘What are you gonna do? You gonna put me up on your bike?’ And then everybody was like, “Oooohhh!” -because he didn’t have a car- (laughs) and I said, ‘You think you’re a man? Why? Why do you think you can speak to me like that?’ And again, everybody went, “Ooooohhh!” He liked being the giver of the joke and trying to embarrass somebody, but when the shoe was turned back around on him, the next thing I know he’s in my face. I said, ‘What are you gonna do? You’re a man, now? You’re in my personal space. You need to step back.’ And then, of course, he stepped back. He liked to try to embarrass me, and when I slipped it back on him he didn’t like that. His buddies were, “Oooooh! Man, she got you!”

Q: What’s good for the goose is good for the gander, eh? (laughing)

SV: Yeah, but for the most part I met a lot of great young people and I’ve reconnected with them on Facebook. I think about Rob Zatechka, because I was in charge of the Student-Athlete Advisory Committee for all the sports, and he was from football. We were very excited about it.

Q: What was the Committee’s general function?

SV: Well, they were to be a liaison between the Student-Athlete population and the administration. Because who knows better what the student-athletes are going through better than the student-athlete population?

Q: Do you recall dealing with any issues in particular?

SV: Well, we dealt with a lot of NCAA legislation. We dealt with some other things, too, but they wanted to have a standard penalty for student-athletes who didn’t go to class or missed study hall, so they couldn’t play or miss a competition. And I don’t know if they ever achieved it, but they tried putting together legislation that no matter what your sport was, if you got caught missing class your week of competition you had to sit out for whatever. When they submitted it to Bill Byrne he said he felt like he didn’t want to impose that on all the teams and that the coaches should make that decision. But the football program, they had that point system and the Unity Council and all that. So the football program was already policing themselves to a degree. And if you got so many points you would not get to play or you would have to sit out a quarter. Sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn’t. And that’s one of the things that existed: they had the point system. But the coaches could always overrule them.

To be continued tomorrow….

Copyright @ 2013 Thermopylae Press. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credits : Unknown Original Sources/Updates Welcomed

Author assumes no responsibility for interviewee errors or misstatements of fact.