Anatomy of an Era: Kent Pavelka, Part 1

Excerpted from Chapter 103, No Place Like Nebraska: Anatomy of an Era, Vol. 2 by Paul Koch

I’ve just gotta tell you: If Nebraska is the “offense of the 50’s”, they must be referring to the average score…

-Kent Pavelka, Nebraska Radio Play-by-Play Announcer, 1996 Fiesta Bowl

Arriving at our final interview, my affinity for the work of Nebraska-raised novelist Willa Cather -winner of the 1923 Pulitzer Prize for fiction who grew up in Red Cloud and studied in Lincoln- should by now be rather apparent. In Robert Bork’s seminal work Slouching Towards Gomorrah, mention is made of her rigorous course load at the University a full century before the great 60 & 3 era came to be, yet it mirrors the load placed on the many of the student-athletes in this tome.

Although the educational offerings may have changed over a span of years, this should give one a good grasp of the busied pace at this institution of higher learning: “…future novelist Willa Cather’s studies at the University of Nebraska in 1891 included three years of Greek, two years of Latin, Anglo-Saxon, Shakespeare and the Elizabethans, Robert Browning and the nineteenth century authors (Tennyson, Emerson, Hawthorne, and Ruskin), French literary classics, one year of German, history, philosophy, rhetoric, journalism, chemistry, and mathematics.” In other words, greatness often comes at the price of great toil, and Cather’s My Antonia and O’ Pioneers! -both pinnacles of literary effort- to this day remain standards of work to which one can aspire.

In the same high-reaching spirit, we conclude with a conversation between myself and Kent Pavelka, a toiling wordsmith and the voice of the Huskers in those glory days. His rapturous and passion-filled “Touchdown, Touchdown, Touchdown!” still sets my hair on end these years gone by, and is a voice that brings to memory many autumn Saturdays.

I recall bucolic and halcyon afternoons of my youth listening to those Husker contests on a farm tractor’s AM radio while plucking potatoes from among the clods of overturned dirt, hauling corn and soybeans fresh from the harvest field, and endlessly kicking a football over the barn and back with Kent, Gary, Lyell and the boys as my all-seeing, all-knowing narrator of the places I would much rather have been. Affixed to my rural locale and conjoined teen angst, the radio troupe were nothing less than spiritual tour guides, lifting me up to heights unknown, somewhere, anywhere…their voice rapid and euphoric, emotions raw and rhythmic.

Kent came to represent Nebraska Football for a generation of fans, the consummation of his all-consuming dream. Like the statue of The Sower atop the Capitol building just nine blocks south of Memorial Stadium, Kent dispersed the seeds of Cornhuskers’ heroics, their struggles, their highlights, their victories, and even a rare vanquishing. His is a voice carrying a time-worn tenor worth paying heed, revealing to us once more the dynamic of that special time and place.

Notable quote #1:

“So many people are conditioned to think that to show passion you have to show crazed passion.”

Kent Pavelka

Question: Hey Kent, from the sound of things you’re on the road already today.

Kent Pavelka: Yes, I just got on the interstate.

Q: So where are you coming from and where are you driving to?

KP: Well, I live in Omaha. I always lived in Omaha back in those days (though I grew up in Lincoln). I’m heading to Lincoln to watch some spring practice right now…

Q: How do you suppose that experience will be in comparison to the old radio booth? Different or the same?

KP: It’s not different, Paul. It’s not different in terms of how I feel like I need to prepare. I’m probably over-preparing, you know. I’m not doing the play-by-play and I won’t be on that often, but you just never know when you’re gonna need to know something, you know? (laughs)

Q: Well, I really appreciate your making some time for me. I hope you don’t mind me delving back into those ’90’s years and what you gathered from that time about the culture & the mood of those teams from your own unique vantage point. How did you get involved in radio?

KP: Well, I grew up in northeast Lincoln and, you know, I was born in 1949 so I was in grade school and remember the days before Devaney got there. I remember as a grade school kid on Saturday afternoons playing touch football with my buddies; through grade school and junior high school as the Jennings era ended and the Devaney era started, Saturday afternoons playing touch football in the backyard with the radio on the window sill inside the house and the window open.

And the Huskers were playing on the radio as we were playing touch football. I was just smitten with the magic of hearing those games on the radio and, in retrospect, I knew then that I wanted to do that. Growing up in Lincoln and then high school and going to college at the University, I identified that as something I wanted to do from a pretty young age.

Q: Were you thinking TV? Radio? Any one particular broadcast medium?

KP: I was thinking of being the Voice of the Huskers on the radio. Absolutely. I thought that was just magic.

Q: Wow, that’s a laser beam-like focus at such a young age…

KP: It was, but I don’t know that it was so unusual. The unusual part was that things actually fell into place and I actually had enough luck and serendipity in my life to do what I focused on doing, you know?

Q: I assume you were a Journalism major. What year did you graduate from the University of Nebraska?

KP: 1971. I finished college in ’71, so I was there for those first two national championships. I actually was a student, and then my first job out of college I got a radio play-by-play job in Fremont, Nebraska. And actually, that second championship on the 1st of January in 1972? I was actually employed at KRNU for that second one. But I spent about three years there in Fremont kind of honing my skills on the radio doing football, basketball and baseball play-by-play for the Fremont high schools, Midland College and the Legion baseball team, and then just happened to luck into an opportunity to go to KFAB in 1974.

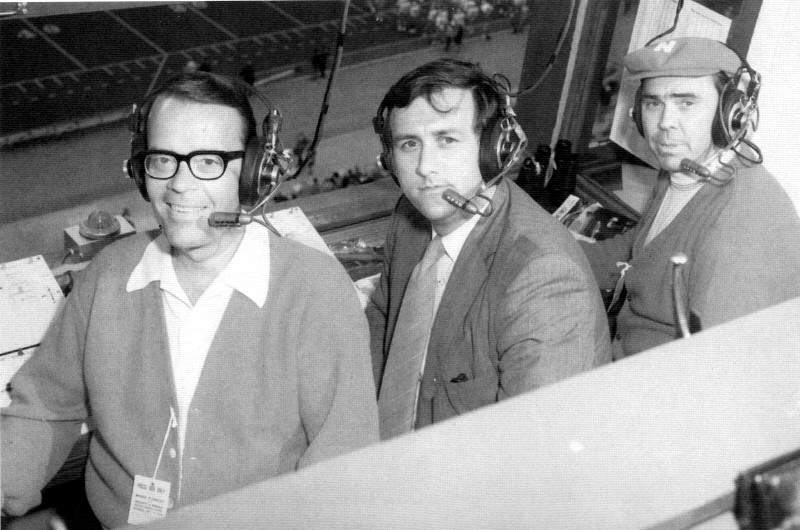

And you know, they were one of four stations at the time that were broadcasting Nebraska football and basketball, and like I said, a lot of it was just luck to be in the right place at the right time. So I wound up there in the booth with Lyell Bremser in 1974, the first year doing the Huskers as the color commentator with Lyell. Then that winter they put me in doing basketball play-by-play. I spent ten years with Lyell doing color in football before I got the chance to do football play-by-play in 1984.

Q: I’ve got to ask, in your mind what is the great difference between color and play-by-play? Is there a special mindset unique to each?

KP: Well, they are just different skills. Every color guy from my era wanted to be a play-by-play guy. I did the color job because Bremser was doing the play-by-play. (laughs) The so-called color job on the radio has kind of given way to more of an analyst’s position. And the things I did on the air as the color guy is different than most of these players who have these jobs now: former players, they’re more technical in terms of breaking down the game than I was. I commented on different kinds of things than what these guys do now. I tried to add things that Bremser didn’t see rather than try to be some sort of football expert. I tried to embellish the picture the listener was getting.

Q: Create more atmosphere, so to speak?

KP: Just kind of fill in the blanks on a certain play that maybe Bremser didn’t see. But as far as the difference between the two jobs, it’s night and day. The play-by-play thing was always the real attraction to me: to grab ahold of that challenge to describe to people who couldn’t see it on the screen, what was going on. And the objective was to paint the mind’s eye view of the game. And the listener wasn’t even aware that they had a mind’s eye view, you know? But that’s what you tried to do was paint that verbal picture, and that’s a real challenge, you know? You need a real creative eye.

Q: I once heard legendary Al Michaels tell the story about how he -as a kid- honed his craft by announcing the contents of his parents’ refrigerator to his mother as she cooked in the kitchen. (laughs) And how did you, knowing that it was your task, how did you work on that skill or develop your technique?

KP: Well, I did basketball uninterrupted from 1971 through 1984 in the winter after football season; I did play-by-play basketball. And so, for those ten years I spent with Bremser, it’s like anything else. After ten years away from football play-by-play, you jump in there and you’re not as good as you want to be. But I learned a lot from him in those ten years in terms of what I felt was the important way to do it and that’s different than what a lot of guys are doing now.

But like any profession, to answer your question: how do you develop the skill? You do everything you can possibly do to prepare. And that includes a lot of different things. In the end, though, when it’s time to go on the air and do the games, all the preparation… you’ve done everything you can, but nothing substitutes for the experience of doing it and the focus of trying to get better at it every quarter, every game, every season.

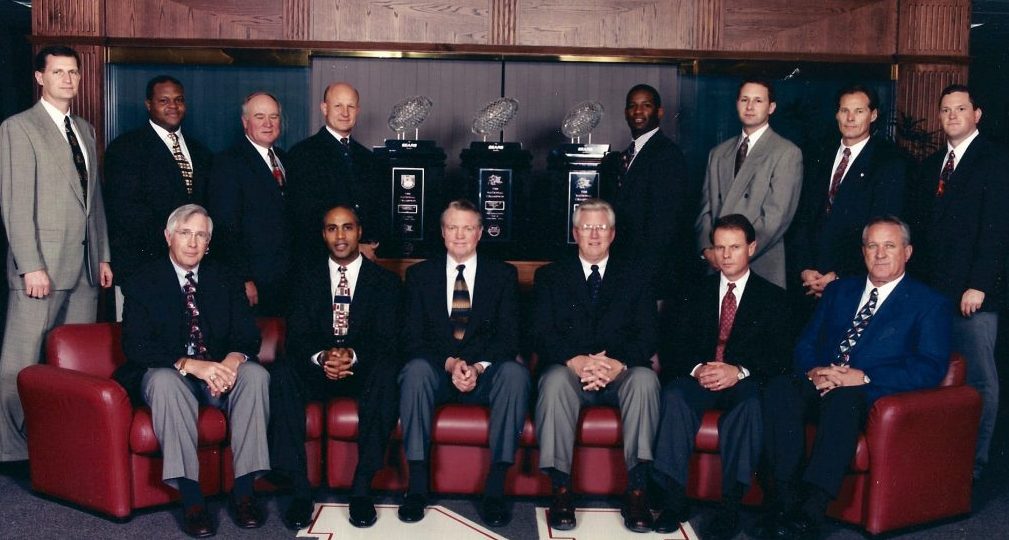

Tom Osborne and staff 1997

Q: I liken it to how Coach Osborne and the staff would prepare –maybe even over-prepare, if there is such a thing- to cross every t and dot every i, and then it was just a matter of rolling with the punches and making in-game adjustments, right?

KP: That’s just perfect, yeah. When I was doing Husker football I would start out on… I mean it was a seven-day-a-week thing, just like the coaches. And that’s the interesting thing about this job, it sounds so easy and people turn on the radio on Saturday and there it is, a radio broadcast. “How hard can that be? You just talk about what’s going on, right?”

Q: And you get paid for it, too…

KP: Yeah, you get paid for going to games, “It’s a party!” (laughs) I’m not saying it wasn’t extremely satisfying and fulfilling, but that’s the frosting on the cake. Doing the game, I would start out as soon as the game was over and drive or fly back to Lincoln, and then Sunday morning get up with the Sunday newspaper and I would read everything I could get my hands on from Sunday morning to Saturday before kickoff, including newspapers, sports information releases, etc. And now, that would include anything you can find on the internet. I would make copious notes. I would have typed out -not computer aided- but 8.5” x 11” typed pages of 150-200 points of just “things,” points of reference about the next game. And I would go over those and go over those.

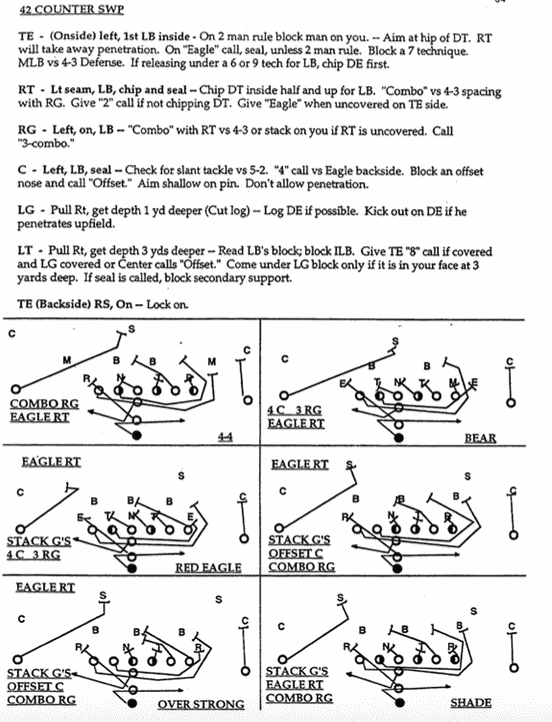

I would talk to coaches during the week I would talk to Milt (Tenopir) and I would talk to George (Darlington) and talk to Dan (Young), and our relationship was such that they trusted me implicitly. And on Monday or Tuesday they would tell me or give me all the information about the next opponent and their sets and plays and personnel, adjustments we were going to make offensively and defensively. And I would study the playbook (even though it was beyond my understanding), but I wanted to identify every set that I could when they broke the huddle and they’d come over the ball. It was just important for me to able to understand, ‘Oh, the wingback in this set is a little bit flanked out further than usual, so that’s called the Pro I Set, but in this set there’s a slotback slotted out wide next to the split receiver and they call that the I Slot Set, or whatever. And over time all of that stuff served me well because I was able to kind of educate listeners as to what those sets looked like, and it helped people as they were listening to get a feel, that mind’s eye view, of what the line of scrimmage looked like before the snap.

Paul, they would tell me what plays they were going to run! They would give me their script! And I would know ahead of time the first couple series of plays. Like I say, to make a long story short, it was that kind of focus from Sunday morning to Saturday at kickoff time, and then I’d just go into another zone and really try to focus and represent this game as best I could to people who weren’t there. That was the grind of it and the joy of it.

I took it really, really seriously. Maybe too seriously. I thought it was real important. For the people who couldn’t be there to experience the games, I wanted them to experience it as close as possible.

Q: That’s so funny, Kent, because the other night I watched a replay of the ‘95 Fiesta Bowl with your voice-over and I specifically recall being impressed with your description of the various offensive sets the players were lined up in. And now I come to find out that you were directly keyed in to the coaching staff, so what you just said now makes perfect sense as to how you knew so much about some of these imaginative sets Coach Osborne would come up with…

KP: Yeah, it was great. And Ron Brown helped me out a lot, too. Back in the day, before the first season, I remember going down and spending hours with Gene Huey and some of the old staff and they would point out the subtle differences in sets.

I was like a football student. It tried to be. So all that was cumulative. I’d go over notes from ten years ago; I always felt like it was a test. You never know when something’s going to come up on the field to jog your memory and bring up some obscure point that was made or somebody told you about.

Q: In other words, you could act as a reference, as a Husker historian, with some of those inside, detailed bits of information over the years.

KP: Yeah, if I’d taken notes, maybe. If I had them organized. (laughs)

Available on Amazon.com

Q: Let me ask you, was there a certain time that it seemed to blossom as far as all these different sets coming out of nowhere, surprising you what was in the playbook? I don’t remember some of these power sets until the early nineties…

KP: Things evolved in terms of the offense and maybe even more so with the defense, as you think about those years. I think Charlie (McBride) brought a real big change to the defensive side of the ball and maybe even more dramatic changes than the tweaking that Tom did to the offense. I think the thing that bloomed… sure, he added some things and things evolved, a lot of those things were just evolution of the game and Tom’s feel for what changes he wanted to make… but a lot of that, too, was to embellish the abilities of his players, you know? Because there’s no question the talent level in his last years was the pinnacle of his career in that respect, so all that stuff looks a lot better when you’re able to execute it, you know? (laughs)

Q: It’s one thing drawing it up on a napkin and it’s quite another having the talent to carry it out, huh?

KP: It was the perfect storm in that respect. He had the great system. It was so unique in so many ways from what most everybody else was doing around the country offensively, and he had the best players in the country to execute it.

So he had everything covered, and it took him a long time to get all that put together at the same time. I don’t know that he was necessarily a better coach in those days, but he had better players… some of those years he wasn’t able to beat Oklahoma. And what I find very amusing back in those days was that nine and three got to be a tired record, an unappreciated record. But in some ways in those days when they would beat Oklahoma and would go to a bowl game and win that ninth game for the bowl game, I think he did his best coaching in those earlier years because he was out-coaching people with players that weren’t as good. Everybody probably points to the championship years, but little do they realize his best year might have been ’87 or something like that.

To be continued….

Copyright @ 2013 Thermopylae Press. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credits : Unknown Original Sources/Updates Welcomed

Author assumes no responsibility for interviewee errors or misstatements of fact.