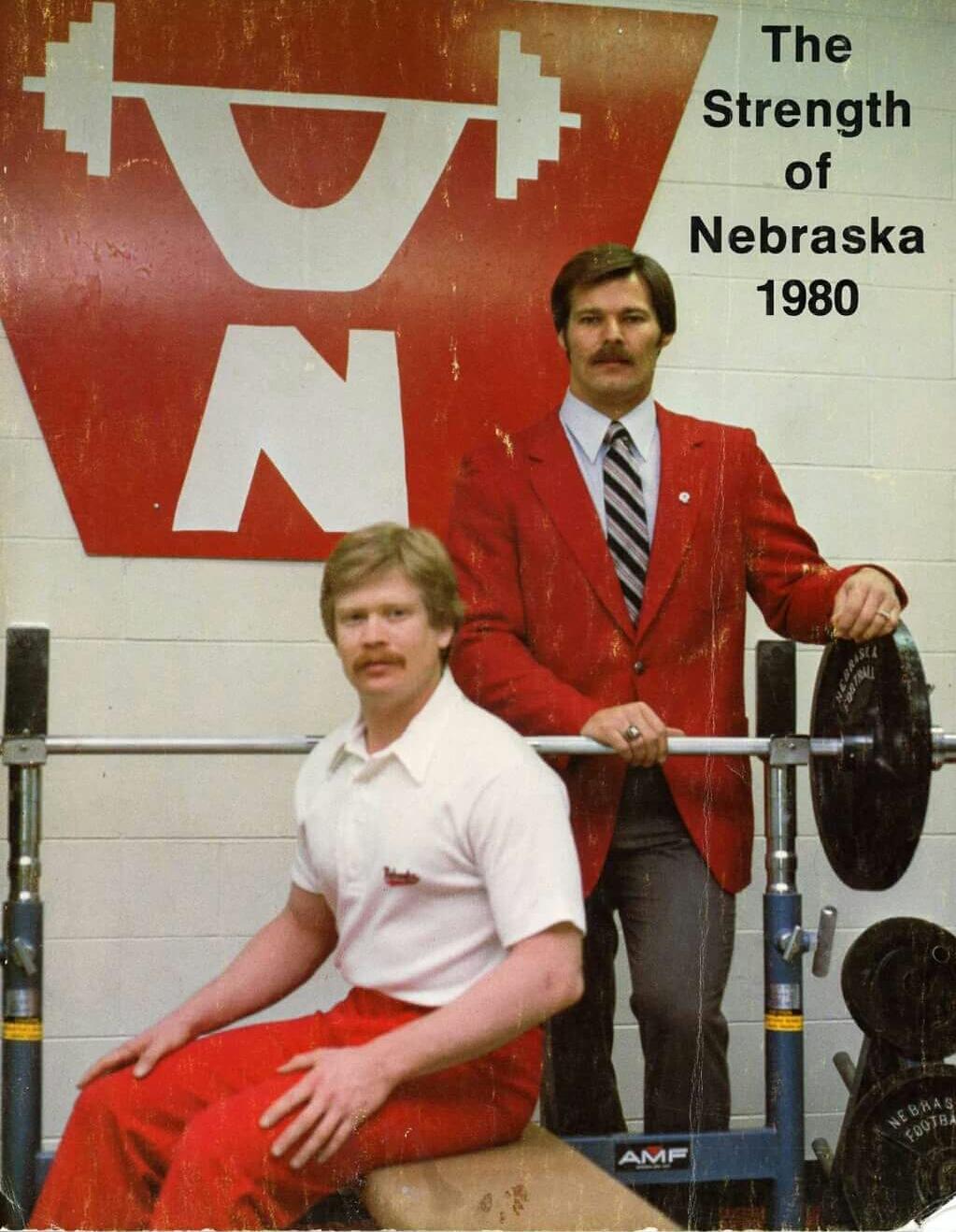

Anatomy of an Era: Boyd Epley Part 2

Excerpted from Chapter 5, No Place Like Nebraska: Anatomy of an Era, Vol. 1

Boyd Epley Part 2

The Godfather of Collegiate Strength & Conditioning/Husker Power

Boyd Epley: (Speaking about the pivotal 1991 Winter Conditioning program) It’s incredible the progress they made. Coach Osborne called me in when we lost the two players. He explained, he said, ”We recruited these young men. We were in their house, the homes with the parents, their families, and you kind of run these kids off.” I said, ‘That’s not the case. They committed to doing the program. They committed to doing it and it’s their choice.’ He said, ”Well, I’ll be really disappointed if we lose any more kids.“ So I was in kind of a tough spot there. Nobody was trying to run anybody off of the program, but the end result was Coach Osborne really got back a football team. He got a disciplined group of athletes who worked their tails off and made great progress.

So when the winter program was over they went into spring football and they kind of reverted back to their own ways. (They didn’t have the same rules. The rules were only for the winter program.) So somewhere along the line in the spring Coach Osborne called me into the meeting room with all the football coaches and said to me, ”How do we get that discipline back? You really had this thing going in the winter and we recognize that this is a great thing, but we kind of slipped back a little bit here.” I said, ‘The punishment didn’t do them any good all those years.’ I was the guy who gave the punishment all those years as the strength coach to Osborne, and before him, Devaney. ’Punishment is a negative thing and it just doesn’t.. it’s not effective.’ And he said, ”Alright, what do you have in mind?” I said, ‘You know on your driver’s license that you have a point system? And you have a little bit of flexibility, and if you do well and get some points back on occasion? You could probably have a traffic ticket or something, but you can overcome that if you have good driving record and get some of those points back. See, you can accumulate some points, but it doesn’t end your career.’ That was maybe, probably a little drastic, where if you were off the team if you missed more than once, you know?

So I came up with this -right off the driver’s license concept- if you miss a workout you forfeited a point, if you miss a practice you get two points, or a meeting or anything that might possibly come up, a class you’re supposed to go to, a certain number of points. So we came up with this point system right on the spot. So Coach Osborne then went around the room to each coach, if they wanted to implement this system, and he went one by one and asked each one of them. He didn’t just say, ”Let’s give this a try.” He looked at each one of them right in the eye. So they agreed to give this a try.

The punishment part of it? We didn’t get that quite right. The punishment was if you got a certain number of points you had to go before Coach Osborne. Well, if you recall, Coach Osborne was a legend in the state of Nebraska and across the country, and getting to go into his office and talk to him one-on-one was not real punishment -it was more of an honor, to be honest, you know? So that didn’t work as well as I thought it would. So the first year we tried to do it that way, but it didn’t have quite the effect I wanted it to.

So the next year I got together with Team Psychologist Jack Stark and we created the Unity Council. The Unity Council was set up to look at who has the points. If you got enough points you had to go before the Unity Council and explain yourself. And the Unity Council was made up of players at different positions on the team, they were considered leaders on the team. They had other purposes, too, they entertained ideas that might be good for the team, if someone had a gripe about the music in the locker room they would bring it before the Unity Council. So Jack Stark was kind of in charge of the Unity Council, but he was from Omaha so he couldn’t be there all the time. So I took the meetings’ minutes and I presented the minutes to the coaching staff the next day.

The meetings were like on Monday nights or whatever. Between Jack Stark and I we kept it together. I presented the points and kept the points, and Jack would have the larger part of the meeting when he was there. The Unity Council had a good impact on the team, and athletes who had some frustrations that might normally build up into more than it should be were able to get it off their chest and get it resolved right away. Coach Osborne would listen very carefully to what they would bring up and their concerns. And he made sure -now, he was a players’ coach- he made sure their concerns were heard and dealt with. It was a good thing. He treated it with respect and they treated it with respect, and Dr. Stark did a good job, too. It helped with the point system and gave the point system a strong impact rather than just going to Coach Osborne by himself, you know. It worked out real well.

Q: I remember when that was being implemented. There were a few hiccups, some guys weren’t buying into it with a lot of whining and complaining, but they came around and really bought into it…

BE: What I liked about it -and I was on both sides of this- I was in charge of the discipline when I saw it wasn’t working and then I was in charge of the winter program where there was incredible discipline. But it was too intense, they couldn’t carry it on for a long period of time. It worked great for six weeks. So what I liked about the point system was that it gave the athletes a little bit of flexibility, where they could miss a workout or miss a class and they wouldn’t miss a football game, but if they missed 3 or 4 things it added up real fast, and pretty soon we had players that actually were held out of games. And it was really their responsibility.

What it did, it really treated them like adults. You know, if you have two or three speeding tickets, pretty soon you weren’t going to have a driver’s license. It worked just the same, the same concept. It didn’t matter who recruited you, it didn’t matter if you were black or white or whatever. It was fair. And for all those reasons, it worked.

The fruits of Boyd’s labors (Nebr. Sports Info)

Q: Before that big commitment meeting, when you went in there to call them out, where did you get that spiel from? Did you already consult with the coaches, with Coach Osborne?

BE: Well, when I realized in 1990 -this one player who ended up being drafted number one, in the first round- had 140 absences, where we were averaging 30 absences a day. We were averaging 30 players missing a workout a day, and I knew that without discipline the program was not working. We tried making them run stadium steps, we tried gassers, we tried them rolling so many yards down the field, we made them throw up doing things like that. One punishment we had was doing hang cleans with dumbbells. We tried any type of discipline that every other school has ever tried. And you had to be safe when you do something like that, it couldn’t be ridiculous. But that type of thing wouldn’t work; some would rather do the punishment than the workout.

It’s all a matter of attitude. So during the course of all that I was looking at all different kinds of options, and I got to thinking about the driver’s license and how fair it was. And Coach Osborne was accused once in a while of favoring a player or another, those kind of comments can turn into racial tension if you look at it that way. Coach Osborne was always fair, very fair. If someone got disgruntled, they could accuse the head coach of playing favoritism: “That guy, he only got punished and had to run two laps. I did the same thing and I had to run 4 laps!” You hear those kind of things. So we were looking for something that was fair no matter who you were: black or white, what part of the country you were from, whether you were a Nebraska guy or not, a senior, a freshman, a walk-on, a star player, an All-American, a Heisman player, it didn’t matter. This system was fair. That’s what he needed. He needed something like that that would have a little bit of teeth in it. Not so much that we were running players off, but a system that was fair, equitable, gave the players a little bit of flexibility, treated them as adults, and made it be their choice to do the right thing. And I think it really hit a home run.

I had a plan, I drew it up over in the West Stadium conference room. I had Mike Arthur come in and look at it and then I went over to the football team meeting. And when Osborne asked me what I had in mind I went to the board and I wrote it up there. I don’t remember the change that we made, but there was only one change. It might have been two points for missing something rather than one, but out of twelve things there was only one change. It didn’t change after that for many years.

Q: So you brought it in and the staff bought into it and the rest was history?

BE: And then the next year Jack Stark got involved in creating a Unity Council, so we had somewhere we could send these players who accumulated points. (To be honest, Coach Osborne was almost too nice to them. He was a very considerate man, and what they really needed -instead of having a father figure that was real considerate like he was- they needed someone that’s kind of gonna give them a little firmer tone, like Christian Peter or a Jason Peter or someone like that, who’d say, “What the heck are you thinking here!?”) So the players on the Unity Council were pretty tough on these kids who accumulated too many points, who weren’t doing their job, who were letting the team down. And they were much firmer, much tougher than the coach was, if you get my point.

Q: Studies have shown that to be true. Have you ever read the book ‘Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion’ by Robert Cialdini, a professor at Arizona State University? He wrote a wonderful little book on human thought/tendencies and motivation, why people do what they do, and even how to persuade them to do what you want them to do…

BE: Haven’t heard of it. But one thing: the freshman that were in that meeting on January 17th, 1991? Those freshmen ended up winning the national championship in ’94. The offensive linemen: Brenden Stai, Rob Zatechka, Zach Weigert, those guys were all freshmen in the meeting that day.

So what happened, they made all the progress in 1991, but they weren’t quite good enough to win the national title when they played Miami and Florida State and so forth, it took them a couple years to put it all together. But as those freshmen carried on this discipline they became almost unbeatable, they really were a talented group of kids through ‘97 there.

Boyd Epley and Mike Arthur (Undcredited/Unknown)

Q: Let me ask you: being a college athlete yourself, what was your first impression of the University of Nebraska?

BE: My first impression was when I came to visit Frank Sevigne, the head track coach, with my parents. My parents actually lived in Nebraska and I was in Arizona. We moved to Arizona and I lived there 10 years, but toward the end of that ten year period my dad got a job putting roofs on the housing for the Air Force folks. He had this roofing contract, so he was up there 2 or 3 years doing this big project. When I got the scholarship offer to Nebraska my parents were already living there, so I came up and stayed with them that summer. So when it came time to come down to the school they brought me down because they wanted to look around, and we went up the track office and met Frank Sevigne. Of course, I met him one time when he recruited me. He came to Arizona State for a track meet and he knew I was a junior college pole vaulter in town, and invited me over to ASU to do a workout so he could look at me. So I just happened to have really good day that day. I jumped higher than the ASU pole vaulters did that day, and Nebraska didn’t have much of a school record; their school record was 13’ 7” at the time, and I was jumping 15’ 1¼”, which was the national junior college record. And so I jumped over 15’ that day, and he walked up and says, ”Are you interested in Nebraska?” I said ‘Yes.’ He said, “I’ll send you the papers”. I wasn’t sure what he really meant, but later a scholarship offer came in the mail, so I signed it and sent it in.

Then I went with my parents to visit him and he gave us a little tour, walked around. You knew Nebraska was a big school. I came from a junior college where they didn’t have the big stadium, the big buildings like Nebraska does. I was impressed with the campus. And I went over and they introduced me to trainer George Sullivan, and George said something like, ”How high are you doing?“ And I said ‘Oh, around 15 foot’, and he said, “Don’t worry, Coach Sevigne will have you down to 14 foot in no time.” (laughs) So I could see they got along pretty well and it was a nice, family environment.

George wasn’t the head trainer at the moment, it was a guy named Paul Schneider. George had a friendship with Frank Sevigne, so he went to the away track meets and had a special interest in the track athletes. So when I’d have to get my ankles taped, George would be the one to do that. George is a special guy. I’m not sure how to describe it, but when he grabbed ahold of your ankle it would just make you feel like you were in good hands. And he’d tape that ankle up, he just did it in a way that you felt comfortable that he did a great job every day. Very comforting, you know? So, I remember that very well, meeting him and having a little tour around the facilities.

Track was exciting, pole vault was exciting, but I really had a disappointing career because I got hurt. I went out and set the Nebraska school record right away, the first meet. I went 14’ 6” or something the first meet. They had to put the standards up on some straw bales because the standards they had wouldn’t go to 14 foot. They had some old ones, so when Coach Sevigne saw that he ordered some new ones that went to 19 feet. The world record at the time was only like 17, and so he got these real fancy standards, so the sky was the limit. (We tried to pysch out the visiting pole vaulters by setting it as high as we could, so when they’d walk in and see the bar up there and go, “Wow, I’ve never seen anything like that!” But it didn’t do much good.

Q: What about the people of Nebraska?

BE: Well, I had a lot of visitors when I was overseeing the strength program, and the visiting coaches would always marvel at the work ethic of our athletes. And they came to try to copy the Nebraska program -the Tennessee State coach visited 3 times, and Virginia Tech, you name the school- they came to study what Nebraska did and why we were so successful, but they weren’t able to duplicate it when they went back home because the Nebraska athletes had this tremendous work ethic.

And a lot of it had to do with Coach Osborne’s philosophy. He had a running attack, so he recruited athletes that would be aggressive and physical in the running game. If I had a strength program at another school -let’s say BYU, known for its passing game- if I would have been at a school like that then I wouldn’t have had the success or the recognition like the Nebraska strength program, because the head coach wouldn’t have needed it as much. In Coach Osborne’s case, my philosophy blended right in with his philosophy, because when we got strong it enhanced his ability to run. And he relied on that strength, and he told those players that in the fourth quarter, “..those times you’d only get 2 or 3 yards in the first quarter, by the 4th quarter you’re gonna dominate and we’re gonna get 7 and 8 yards. You’re going to dominate and we’re gonna control the game.” And that’s exactly what happened.

Copyright @ 2013 Thermopylae Press. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credits : Unknown Original Sources/Updates Welcomed

Paul Koch