Anatomy of an Era: Aaron Davis, Part 1

Excerpted from Chapter 60, No Place Like Nebraska: Anatomy of an Era, Vol. 2 by Paul Koch

“The thing about football –the important thing about football- is that it is not just about football.”

-Terry Pratchet, Unseen Academicals

Competing with Sir Mix-A-Lot’s Baby Got Back in 1992, the top song of the year was Boyz II Men’s End of the Road, which spoke of a lasting fidelity forged despite heartache and disappointment, of an intimate association of affection and proximity built up through the years, a never-ending love affair between a young man and his eternal flame. Such was the case of Aaron Davis and Nebraska Football.

That flame burns brightly still today as he crisscrosses the country’s roadways inspiring all walks of life through his engaging, insightful, and oftentimes hilarious sharing of the lessons learned, the hurdles leapt, the laughs & the tears of the trek, and the process of championship ascension. A football philosopher and a jester among the jerseys, Aaron brought a unique personality to the receiving corps. Listen in on a few worthwhile and enduring principles that he gathered along the route.

Notable quote #1:

“It was the weight room… that’s where it starts. To physically become stronger and dominate people physically, the weight room was the place where you went to improve, it’s where boys came to become men.”

Aaron Davis

Walk-on, Split End, Lincoln, NE (Lincoln High)

Where are they now? Lincoln, NE, Motivational Speaker

Question: So Aaron, you’re traveling around the entire country giving motivational, inspiring and informative speeches about being successful these days, eh? And I hear you’ve got a book coming out, too?

Aaron Davis: Yeah, I have a couple out. One was titled ‘Ten Minute Truths’, and I have another one about customer service, as well: ‘Wisdom from the Man with the Mop’. It’s about my dad, who was a janitor for 40-plus years. It’s just about ready to come out in a month or so. I’m excited for it.

Q: I look forward to reading it, Aaron. Now, what year was your first fall camp? Can you tell me about that?

AD: It was 1992. And the thing that sticks out for me, Paul? I don’t know if you remember, but Mark Davis was one of the equipment managers at one time. That was my older brother. So I had been hanging around the stadium since I was a kid, hanging around with Jeff Solich, Coach Solich’s son.

But checking in that first day for me was surreal, much like it was for a lot of players, but a little different in that I had been down there working football camps there over the summers. But for me, I was just a shock that I was there. For me, it was almost the exact opposite of most guys, because I was so used to it, but not as a player, and I wasn’t sure if I could get used to that. Shagging balls as a kid and dreaming of playing and then finally getting to do that? For me that first day was just surreal. I remember the smell of that old north locker room, just walking in that old locker room in north stadium with the concrete floors with those big, giant, red, steel lockers. It was just surreal. It was a neat experience. I was just, ‘Wow, this is Nebraska, man!’

Q: Instead of being on the periphery you were actually ‘one of the guys’!

AD: Yeah, that’s a great way to say it.

Q: So when you finally were able to strap the pads on, was there anything that altered your view of Nebraska football? The organization? The practices?

AD: The thing about it was that if you were an all-star or just walking on there and looking for a chance to compete, you felt like you were part of a family.

The way things were done were very systematic. Things were done with excellence: the way you carried yourself, the way you practiced, the way that you prepared. There was a culture of excellence, a culture of high expectations, a culture that mediocrity would not be tolerated. And you know as a strength coach in the weightroom, in the meeting room or on the practice field, there was a way to get things done. You were not only accountable to your coaches, but you were accountable to your teammates. So there was accountability on all levels.

And to get to the level where you could wear that ‘N’ on your helmet? That came with a great deal of pride. And I’ve said it many times before: we didn’t just play at Nebraska, we worked and toiled for the opportunity to play for Nebraska. So when you put on that helmet you were putting on something and representing more than a million people in that state that had supported that program and loved that program so much, and you didn’t take that lightly. And all the sweat and the blood and the tears and the toil that went on that field before you? You not only wanted to not let your teammates down, but you didn’t want to let all the players who came before you down, either, because they played such a huge part in the dominance that we enjoyed for many years. That’s one reason the name ‘Nebraska’ resonates around the country.

Q: And as far as creating that culture of excellence, how would your coaches convey that?

AD: There’s tons of names that stand out to me. As a receiver- and I’ve used this many times in my personal life and in the business world- I remember Ron Brown used to stand not two yards away from you and just throw that ball as hard as he could at you to catch. He would just zing it as fast and hard as he could. Anyway, when that ball was in the air and you were running and could maybe catch it, just touch it with your fingertips, there was always the saying, “When in doubt, lay out.” A lot of times in life some things seem just out of your reach and we don’t want to leave that comfort zone, but “when in doubt, lay out.”

Sometimes you’ve got to be willing to leave your feet, risk it and lay it on the line. And I think that resonates with every position coach; they constantly challenged us to get out of our comfort zones and to do things that we didn’t think we could do, push ourselves just a little bit further every practice. And you may not catch that ball, but at least you have to lunge and try. When in doubt, lay out. As a husband, a father, a businessman, sometimes you’ve got to leave your feet and go after the big one. You might miss it. And often if you do it’s because you didn’t lay out and try. That was just our mentality. We would not tolerate lack of effort. Not only that, but you’d get your head knocked off.

Q: Any recollections of yourself having a bad day or anyone else giving a poor effort? What happened when something like that happened?

AD: I remember one practice where -and as receivers at a time when we primarily ran the ball- us receivers would practice chop-blocking all the time. That’s why a lot of people were so intrigued with Nebraska’s running game, because Coach Brown always used to preach, “Dominate the perimeter. Dominate the perimeter.” And that’s why we had so many thousand-yard backs. Not that they weren’t great backs or not that we didn’t have a great offensive line -but us guys out there as receivers?- we understood that a ten-yard run could be a twenty-yard run, a fifty-yard run, a ninety-yard run if we took out the corners and the safeties and linebackers.

So I remember one practice where our blocking just wasn’t crisp, so Coach Brown said, “We’re going to stay after practice and do some more blocking until we get it right. We’re gonna keep doing it until we put everything into it and do it the way it should be done.” So we left it all out there on the field. It was just a mindset that nothing less than full effort was tolerated. And we realized that that was necessary, because you play the way you practice.

Q: So many guys talk about the practice intensity. Was that a shock to you coming out of high school and even being around the practices years earlier and viewing them up close?

AD: You know, watching it and doing it are two totally different things. The differing intensity levels going from high school to a top-notch program like Nebraska, you can’t understand it unless you experience it for yourself. It would be like trying to tell someone who doesn’t have a daughter or a son yet, you just can’t begin to appreciate it or understand it unless you experience it for yourself. Practice intensity was just amazing, and that’s why we’d dominate teams so much, because we would take it to each other in practice every day. And if you didn’t do it that way, you got your head knocked off.

Available on Amazon.com

Q: Any good examples?

AD: There was one time: Toby Wright hit me so hard one time, I seriously wondered if I should be playing football anymore. (laughs) I remember contemplating it as I was laying on the turf of Memorial Stadium looking up at the sky. (laughs) Toby would hit you. And all those guys would hit; playing for the scout team against the first team every day -the Blackshirts- they put it to you.

Troy Dumas, he hit me so hard one time. I was coming across the middle and he hit me so hard. And the ball was high, but there was no way that you didn’t go after it when the ball was in the air, you just had to find a ladder and go up and get it…

Q: When in doubt, lay out?

AD: Right, you’ve got to lay out. And I knew I was gonna take the hit. And Coach Brown used to tell us, “You’re going to get hit anyway. You might as well catch the ball.” But Troy hit me so hard, I recall that it seemed like it took forever for me to land. I was in the air forever. When we finally hit and his shoulder pads went right up into my chest? That wasn’t for lack of effort… that was just a great hit.

Q: Troy had a propensity to injure people…

AD: (laughs) He definitely did.

Q: Seriously, it seemed so many times Troy would go to hit a guy and he’d just pop up and the guy would always be there laying on the ground writhing in pain. He could seriously ‘bring the wood.’

AD: I remember one time against Wyoming he hit that quarterback so hard, I thought the guy’s head was going to come off.

Q: So were there some close, special friendships?

AD: You know, me and Tommie are still pretty tight to this day. My whole freshman class was real tight, Riley Washington and Brenden Holbein are guys I hung out with quite a bit. Tommie lives less than 5 minutes from my house. We see each other quite a bit. Myself and Clester Johnson all ran together and were really tight. Tyrone Williams, too.

Q: What would you say about Coach Brown? What set him over and above as far as being a special guy?

AD: I would say with Coach Brown -and I’d echo it with Coach Osborne- they cared more about you as a man than as a player. And I say this about both of them: they cared more about your first four years after college than they did your four years in college when you were eligible. And we knew that: we knew they cared more about our next forty years in life than our 40-yard dash, whether we were being good citizens, good husbands and fathers, good business leaders in the community, contributing to society. The championships were nice, but they were more concerned with the four and a half, five years to develop the young man into a grown man and give him lessons and strategies to be successful off the field.

Because eventually the applause stops, and it’s a tragedy for a lot of athletes, especially like a place like Nebraska where it’s at a high level of competition. There’s many who don’t know how to respond when the crowd applause stops for them. And they were interested in helping us find ways to live, to be productive and successful off the field. So it was like they said, “Hey, I have five years to develop this young man to the best of my ability. And after five years he goes away.” So for them it seemed like they had a sense of urgency. They had to instill a purpose into us as much as they could, and if you were an All-American and went on to the next level, that was just gravy on it, but their main purpose was to give us a solid foundation for life after we left there. So I think that’s what separates that Nebraska staff from a lot of great coaches. And to me, that’s why guys would run through a wall for those coaches, because we knew they loved us and they cared about us regardless of football games on Saturdays.

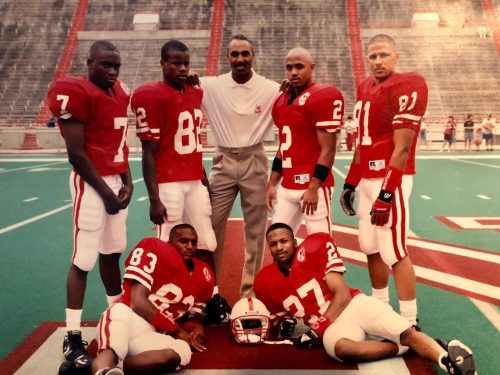

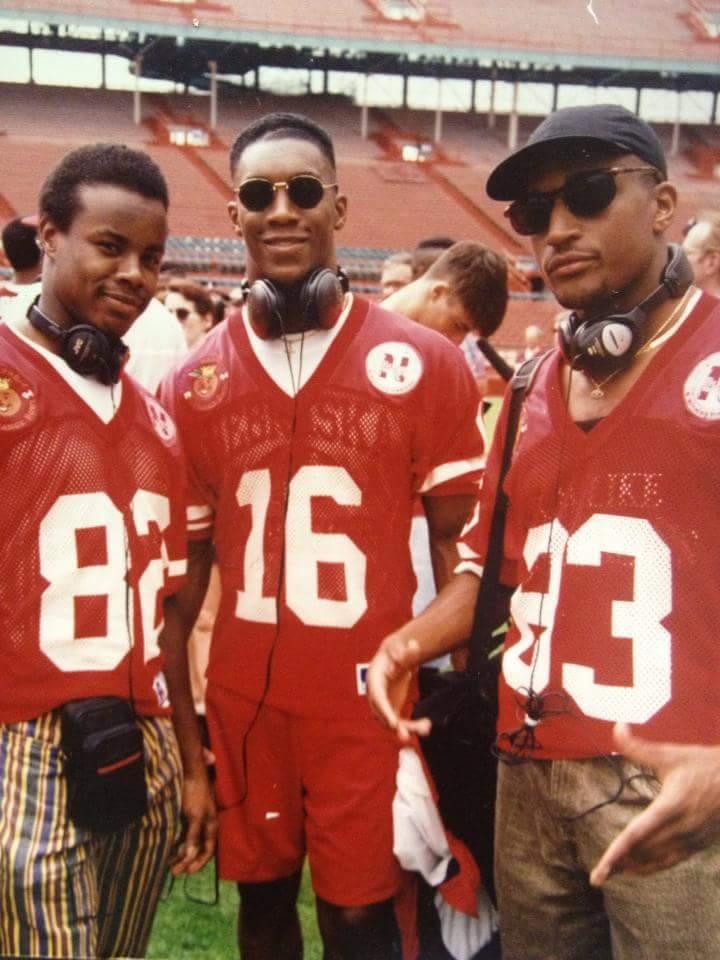

Riley Washington, Eric Stokes & Aaron Davis

Q: Aaron, how was that love & caring best conveyed? Was it something they stated overtly?

AD: You know, it was spoken on a regular basis in many forms. And it was lived out every day. A lot of people can say things, and as kids we were always, “Prove it to me.” I remember a number of times when coaches would pull you aside and talk about life, “How are you doing? Can you improve in this? How is your family situation? How’s your mom? How’s your dad? Is there anything I can do as a coach to help you out and improve things, whatever they may be?” And it was not only on the practice field, but off the field as well.

So that was something that we just knew, that they loved us. They told us that, “We love you guys. We want the best for you.” You just don’t hear that from a lot of coaches. And the commitment they made to your parents, they meant it.

Q: Can you comment on the dynamic between Coach Brown and Coach Osborne? Obviously Coach Brown enjoys being at Nebraska as a mission field in addition to his coaching, but do you think there is anything else there?

AD: I know everyone from Bobby Bowden to Tony Dungy have tried to hire him away. For me, it was good too, because he was a great mentor as a spiritual big brother. He just lived it out, and would encourage you to be spiritual and faithful. That’s something that meant a lot to me. He didn’t lay his conviction on you but he would encourage you and say, “Think about this.”

And for me as a young Christian to the father I am now, a lot of those things help me out with my children today. He would challenge us if we came to him with questions. He would never say, “Hey, we’re gonna talk about God.” We’d sometimes come to him with certain questions and he would tell us what his faith and belief did for him, what the scriptures said, but he would say, “Hey, check this out for yourself and figure out what it says.” There would be times when I was way out of college and I’d call him and tell him what was on my mind or what was troubling me and he’d pray with me, which was so cool. So cool.

Q: And what about Coach Osborne? Most kids, especially as freshman, were scared to death to talk to Coach Osborne, but I have a feeling you weren’t quite as skittish around him because you were a little more familiar with him.

AD: You know, with Coach Osborne, he’s so laid back. You’d ask him a question and he’d be, (mimicking in soft tone) “Well, A.D., yeah, I don’t think that’s a good situation. We just don’t do that here, guys.” (laughs) I still talk to Coach Osborne quite a bit. We both work out at the same gym. But Coach Osborne for me, knowing him for so long? Obviously there was still some reverence there. It was like talking to your dad. There was a level of respect there. There was always the special dynamic there because you just had so much respect for the guy. And not like you didn’t have any less respect for the other coaches, but it’s just Coach Osborne had a persona and aura about himself that demanded respect. And not so much demanded it, but you just felt compelled to respect the man for the way he carried himself and the way he lived his life and the type of person he was.

So you just kind of felt this profound respect for him in a crazy way, because you knew he was always going to be fair and he was always going to be looking out for your best interests as a young man. And I think that’s something that carried over even to the game itself. You had so much respect for him that you didn’t want to let the man down, you just did not want to disappoint him in any way.

Q: Any other coaches from those days stick out to you as to their uniqueness?

AD: I got to know Charlie McBride well, because he had a knee surgery. I think he had about 40 knee surgeries, (laughs) but when I was in high school and I was one of the ball boys and started working football camps in the summer. I would drive him around on those golf carts and I’d be picking up the equipment from down in the pit in the north fieldhouse or the Cook Pavilion. So I’d usually give him a ride from the stadium to Cook Pavilion or vice versa and I got to know Charlie McBride pretty well those summers.

And Turner, too. Turner Gill was the one who started calling me A.D. He kind of started all that off. And he was a funny guy, too, with that deep voice, “Hey A.D.! What’s going in, A.D.?” (laughs) And I remember him as a kid and then when he came back from SMU as a quarterbacks coach. And I was actually up there a few years ago along with Coach Osborne when Turner was at Buffalo and you could just see how he changed the culture there, the expectation in the air. I could see how he changed that firsthand, just walking around the campus. There was that certain aura about the man.

Q: So you walked on. Were you a walk-on the entire time as a player?

AD: You know what I did? I only had the chance to play for three years because the money ran out. And when I came back to play for my last year in ’96, my roommate was murdered. I sat out the year in ’95. What a year to sit out. (laughs) But my roommate, who I was living with, his name was Mike Plescott, he was my best friend since childhood and we were living together. And he was murdered the summer of ’96 by this girl. She stabbed him, man. I was working out and trying to save up some money, was getting ready to play ball again and was talking to Coach Osborne, “Hey A.D., come on back.” And then that June when my roommate was murdered that threw me for a loop. Then things changed pretty quickly and I just wanted to be done with school. When something like that happens it changes you a little bit.

Q: So the ’95 Orange Bowl game versus Miami was, for all intents and purposes, your last game. Anything about that ‘94 team stand out to you?

AD: The thing I think that sticks out the most for me? You should never count anybody out. Including yourself. I don’t care what you face in life, what you’re dealing with. If you give yourself a chance, that’s all you need to do. If you’ve prepared, if you’ve worked, if you’ve studied, totally saturated yourself with the information at hand, whether it be sports or the business world, you’ve got a shot. You can’t listen to what the crowd is saying, you can’t listen to what the people are saying.

If you look at the economic situation at present, Paul, I see a lot of people who have just given up. I’m not saying some people aren’t having a hard time, but you can’t believe everything that’s out there. The reality is: it’s your reality. And that doesn’t mean you’re ignoring numbers and facts and figures and the culture and environment of what’s going on and avoiding the situation right now, but at the same time people are still making money and still building things and still buying houses. Maybe not like it was before, I know that, but things are still being done in a positive role. And I remember the whole month leading up to that Miami game and our practices, all we kept hearing was, “Oh, Nebraska doesn’t have a chance. Miami has too much speed. That old option offense doesn’t stand a chance against a team with such superior defensive speed and dominance.” That’s all we ever heard.

And while we were out there in the sun kicking each other’s tail and sweating, we weren’t going out there saying, “We’re just gonna give it a shot and see what happens.” No! We went down there to win! I tell students that today, people in business today, ‘If you’re not in business to turn a profit, what are you in business for?’ That’s the purpose of business, you can do a lot more with a profit than a loss. You don’t go in business hoping to make it, you are looking to dominate it. Now, you deal with what happens as you come across it, but your mentality needs to be just like Osborne’s in those humid, hot practices down in Miami: you were there to win a championship. You just didn’t show up to have a moral victory. There were not moral victories at Nebraska. There are no moral victories in life; you play to win. If you’ve lost you’ve lost, and you’ve got to move on.

I was flying into Philadelphia today and I don’t want that mentality, I don’t want the pilot to say, “Well, we’re gonna try to land this plane today. But if we don’t, well at least we gave it our best effort.” (laughs) No, you have every intention of landing this aircraft, you know? And that’s the way I look at life as a result of those lessons preparing for the Orange Bowl. It was, “You know what, we are playing to win a national championship and we have every intention of winning.” Losing was not in our vocabulary nor in our mentality.

Even when you go back to that game and the way it started off, some people may have been saying, “Uh-oh, here we go again.” But we were thinking, “It’s just a matter of time. We’re gonna win because we practiced harder than they did.” Paul, to my knowledge, they didn’t even start practicing until a couple days after we were even there! They didn’t think they needed to because the immense amount of talent they had. I was on the scout team for those practices, and I remember us guys saying to each other, “We are going to bust the Blackshirts’ tail each and every day. Because Miami’s not going to give up. And they’re used to this heat and humidity while we aren’t. We have to push the envelope everyday in preparation for that matchup on their field.” Our mentality wasn’t just to go there and have a good time. Our mentality was to go there and win.

That mentality has helped me out in business, too. I’m not starting a company just to do okay. I started this thing to be one of the best out there and to dominate. That’s how I look at things out there in the business world, and even as a father. You know, I need to be the best husband I can and the best father I can. Not just to get by, but to be the best. Do I fall short in those areas? Absolutely! But I can’t go into every day with the intention of, “Well, I’m gonna barely give some effort to day and see what happens?” No! You go to be the best, and that was our mentality. The biggest thing, the negative hype that we always heard, that just pumped us up even more.

Q: There’s nothing quite as satisfying as proving people wrong.

AD: You’ve got that right. There is nothing like coming away from a competition, no greater feeling than to silence your critics. Now, you didn’t play just to silence them. If that’s your mentality, then you’re playing the game for the wrong reasons. You play for the satisfaction and the feeling of completeness that you’ve put in hard work and reaped the benefits of it, seen the results of your labor. And the reality of it is, when you do win championships in life, be it as a father, a businessman, a husband, even if it’s the guy putting stripes on the highway, when you’ve done it to the best of your ability there’s no greater feeling than knowing that you’ve done it to the best of your ability.

You don’t remember the pain as much when you win. Obviously you remember it, but it didn’t hurt as much when you won and you didn’t think about it as much as you do the journey you took to get there. I bring that mentality with me today, I go out there to win.

To be continued….

Copyright @ 2013 Thermopylae Press. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credits : Unknown Original Sources/Updates Welcomed