Anatomy of an Era: Lorenzo Brinkley & Kenny Wilhite, Part 1

Excerpted from Chapter 11, No Place Like Nebraska: Anatomy of an Era, Vol. 1 by Paul Koch

I am a border ruffian from the State of Missouri… In me you have Missouri morals, Connecticut culture; this, gentlemen, is the combination which makes the perfect man.

-Mark Twain

World War I’s General of the Armies John J. Pershing was born in 1860 in a tiny Missouri farm shanty about 150 miles northwest of St. Louis, as the crow flies. First teaching schoolchildren of former slaves, he won entrance to West Point Military Academy and later fought as a Cavalryman against the American Apache & Sioux, then alongside future President Teddy Roosevelt in Cuba at the Battle of San Juan Hill. ”Black Jack,” as he came to be known, was cited for gallantry, extraordinary marksmanship, and his severe coolness under fire.

Soon thereafter in 1891, Pershing began his Professorship of Military Science and Tactics at the University of Nebraska. Spending four years in Lincoln (and earning a law degree on the side), he formed the elite drill company later known as the Pershing Rifles. (A sign commemorating this World War I hero stands just 100 yards to the east of Memorial Stadium at the corner of 14th and Vine Street today) History shows that he first earned the (derisive) nickname “Nigger Jack” – subsequently becoming “Black Jack”- because of his service with the ‘colored’ Army’s 10th Cavalry, and brought a distinct measure of discipline, foresight and leadership to the Nebraska campus (much to the chagrin of the pacifist atmosphere of the day). A mentor to America’s greatest World War II generals, this Missourian of humble beginnings was just a first of many to make a name at Nebraska, where the culture he instilled lives on.

But other Missourians of note also played a role on the Lincoln campus, including a great part of those 60 & 3 teams: players like Mike Rucker, Grant Wistrom, Ed Morrow and Jacques Allen, among others. Which brings us to Husker roommates/teammates Kenny Wilhite and Lorenzo Brinkley.

Both hailing from St. Louis, Missouri, at the time of this interview they were both college football coaches on Tony Samuel’s staff at Southeast Missouri State University. Looking back, ‘Lo’ had the unfortunate experience of a nasty broken arm in the waning moments of the historic 18-16 Orange Bowl Florida State loss, and if not for that abbreviated gameday his presence on the midway just may have swung the tide in preventing Florida State’s final, successful drive. (Again, it’s one of those ‘woulda, coulda’, shoulda’s,’ but I have a feeling the ’93 Husker team would have held Charlie Ward and Warrick Dunn’s heroics in check on that drive had he still been in there knocking heads.) Kenny, on the other hand, had played out his college career a year earlier and was watching that game as a pro in the Canadian Football League. Though off the roster, he’d played a part in bringing the team to that point.

Let’s get ready, hyped and amped for a few bits of insight from two guys who know a thing or two about the Husker’s transformation to dynastic status. This one hits from every angle, converging on the subject as the two Husker defenders often did…

Notable quote #1:

Lorenzo Brinkley: “When we got Toby Wright, I think that changed the whole mental state of our defense: because he’d knock the shit out of you, to put it plainly. So it started to be the game where everybody was trying to knock the living shit out of somebody.”

Notable quote #2:

Kenny Wilhite: “For the most part, you wanted to win it for the coaches, for the hard work they put in. Especially Coach Osborne, you wanted to win for him. You wanted to win for yourself, but you wanted to win it for him.“

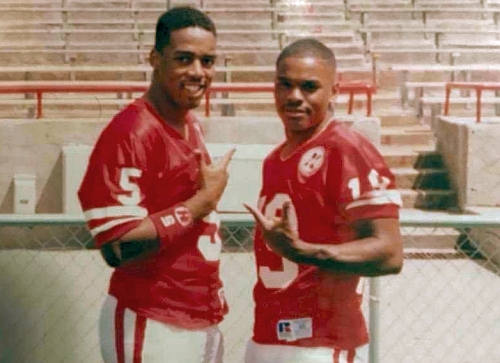

Lorenzo Brinkley & Kenny Wilhite Part 1

Scholarship recruit, Cornerback, St. Louis, Missouri (Hazelwood Central)

Where are they now? Cape Girardeau, Missouri, Coach

Scholarship recruit, Cornerback, St. Louis, Missouri (Oakville)

Where are they now? University of Nebraska, Director of High School Relations

Question: Hey guys, it’s neat to see that the both of you, as well as Troy Dumas and Chris Norris, are now with Tony Samuel at SEMO. That’s pretty cool.

Lorenzo Brinkley: It’s quite the crew here, that’s for sure. A real Nebraska flavor.

Q: So how did you guys end up on the Nebraska campus as young players?

Kenny Wilhite: I actually went to a junior college out of high school, and then the recruiting process started all over again. I narrowed it down to two schools: The University of Pacific and the University of Nebraska. And the reason for the University of Pacific was because John Gruden was one of the assistant coaches on the staff and was the one recruiting me (he actually did great job).

When it came down to making my decision I had to ask Gruden, I said, ‘Hey, you’ve been here to Dodge (Kansas) a couple times to see me. If you can get the head man to come down and visit me at Dodge City and then go sit in my living room -in my living room in my neighborhood where I grew up- you’ve got a great chance of getting me to commit to the University of Pacific.’ Ron Brown was recruiting me to the University of Nebraska and I told him the exact same thing.

Well, needless to say, Coach Osborne showed up on a Thursday morning, we went and had lunch (and he signed about 200 autographs in the cafeteria with no complaints), then flew to St. Louis. He called me when he got seated in my Grandmother’s living room and I said, ‘Coach, I’m going to the University of Nebraska!’ (laughs)

Now, once Coach Osborne saw where I grew up, he said he was gonna do whatever he could to make sure I graduated, and that made my decision a lot easier, also. So it was just a matter of whether I could fit in with the guys there and get a good education.

Q: Did that experience affect how you recruit now, Kenny?

KW: Those three -meaning Coach Gruden, Coach Brown and Coach Osborne- were upfront and they weren’t just trying to sell me a dream. That’s the way I approach it, also, and that’s what I tell the kids straight up. I say, ‘Hey, this is what I expect. This is what I’m gonna do. You need to be honest with me, also, I’m not gonna give you some B.S. I can’t promise you this or that, but I can promise you I’ll take care of you the 4-5 years you’re with me, get you an education and make you a better person. I’m there for you if you ever need anything, someone to talk to or a shoulder to lean on,’ you know? And I learned that from Coach Osborne. Being with Coach Samuel for a few years, he’s the same way, too.

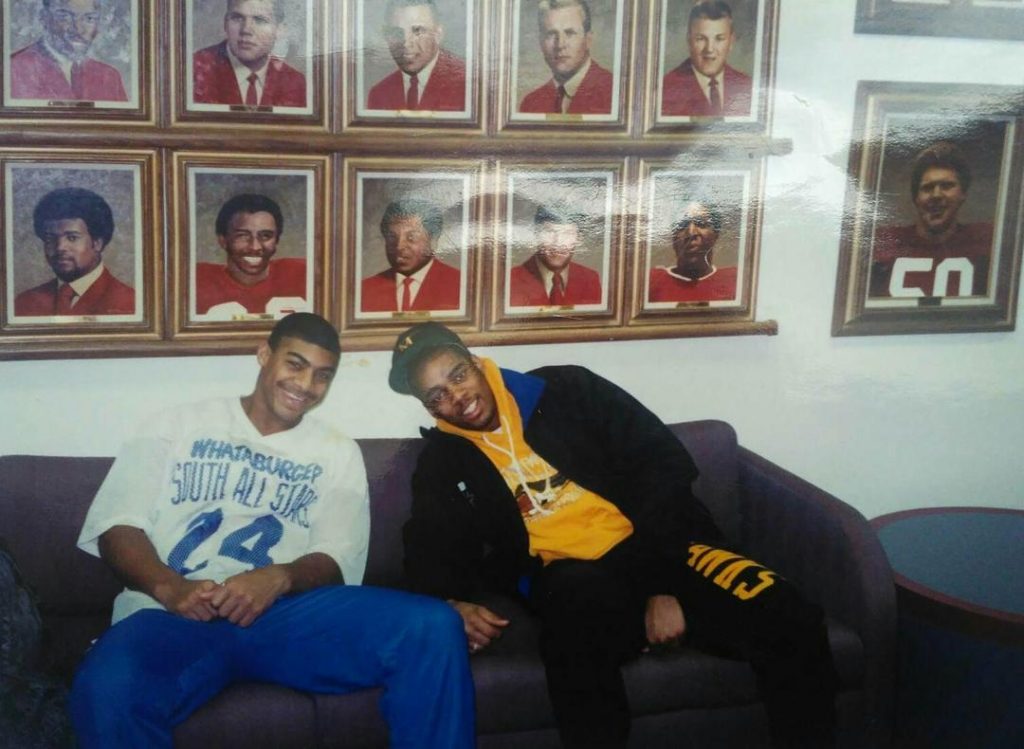

Marvin Callies & Lorenzo Brinkley after an intense night of study (Unknown Source)

Q: When was your first fall on campus at Nebraska, Lorenzo?

LB: It was ’89. We were both there when everything went through a change.

The level of professionalism really stood out to me. At that time high schools weren’t structured like college programs were. It was an amazing deal as far as the organization and the regimenting of time. In high school you just played -you know?- to put it in a nutshell. We weren’t big on the small things in high school, you know? You just showed up and went for the ball. Then it seems like you come to this ‘factory,’ and everything is so technical, it comes down to the discipline and other factors, that was the case.

Q: What was your biggest challenge to overcome?

LB: My biggest challenge was to get over my own ego and try to buy into the system. I think the light started coming on for me when it was finally my third season, actually. I had some injuries and stuff, you know. I broke my wrist my second year there, so I had to wear a cast for a while and I think it kind of slowed my progress. But during my time with the injury I started to pay attention a whole lot more, because I wanted to play. You start getting that competitive thing, and athletically you look at other people in the room and you wonder, ‘Why’s that other guy playing and I’m not?’ You start checking yourself.

Q: A little more self-evaluation in addition to the coaching evaluation going on?

LB: Right, because as a young player I had to side against the coach all the time instead of listening to what he’d tell me.

Q: Did you and Coach Darlington butt heads a lot?

LB: Oh yeah, probably more than we should have. (laughs) I was immature, I’ll admit that. It was a two-headed thing, too, due to the fact that he didn’t really ask to us to buy into the system, to reel us in, because we had so much depth. Initially I was against reaching out for a little guidance at that point in life, and he argued against it.

KW: Coach Darlington was very, very high strung, and I know you know that. And for me, when I first got to Nebraska I was utilized as a quarterback and redshirted and I was on the scout team offense, mostly. (That was in the fall of ’90) So I played a little quarterback during Colorado week, receiver sometimes, quarterback during Oklahoma week. Then because of some injuries they were short on the defensive side, and they said, “Hey, if you want to have a better chance to play at the next level you might want to switch to cornerback”, and that’s what I did.

I only played cornerback sparingly in high school, so it was a learning process. And I tell you what, he stuck by me. He was willing to give me an opportunity to switch over. And Coach D. could be challenging at times, but he’s a very, very good coach. He knows his football.

Q: Challenging in what way, Kenny?

KW: He wanted you to be perfect, and if it’s not perfect he’d let you know.

Q: In what ways would he let you know?

KW: If only you knew. (laughs) You could hear him from one end of the stadium to the other end of the old grass practice field. You could hear Coach D. But he was a good one, he pushed us a lot in practice and I think he pushed us for the best. He wanted us to be the best -not only in the Big 8 Conference- but in the country. He made sure that every step was right, every technique was right, he was a perfectionist.

And when I first got there, my first year it was Shane Thorell, he was the Graduate Assistant in the secondary. He was just getting started, he was working with Coach D. He was a good one and it was like ‘Good Cop, Bad Cop.’ He was the one that would give you a pat on the back. Coach D. would let you have it and Coach Thorell was there to pat you on the back and tell you “It’s gonna be okay” and everything.

Q: Interesting. Do you guys recall the Unity Council coming into being at that time?

LB: Yeah, I remember it. I’m trying to recall, I’m not even sure if I was on the Unity Council or not. But for some reason it seems at that time that I thought I had a whole lot to say. (laughs) It was good, because we did have a void in the communications between the players and coaches. I think it was the start of the change because the players started to feel a lot more ownership.

Q: Things became less adversarial after that?

LB: To a degree. But we also knew at that point that everything was going to get to Coach Osborne instead of just stopping at a position coach. I don’t know how many times they went to Coach with something that maybe they didn’t think he needed to hear or maybe he was too busy for.

KW: I was there when they started the Council. I know for myself I never had to go in front of them. Now, I wasn’t a saint by any means, but I wasn’t going to do anything that crazy to have to go in front of the Unity Council. Either the Unity Council or Coach Osborne or the police? I was like, ‘I don’t want to deal with none of those guys!’ (laughs) You know, you were put in situations. Now, the bars? We did our thing, but we took care of each other for the most part. So if you went with somebody and there were other players there it was like, ‘Hey, Ernie Beler, I’m getting ready to go, it’s getting late. Nothing good happens after 1 o’clock,’ you know?

And I remember that time, that team meeting, too. The workouts in January of ’91, it changed from having guys trying to skip workouts and looking toward the next level -not wanting to become a team- instead of working out as a team. Guys like Dante Jones and Ed Stewart and Dwayne Harris, they were young guys up and coming, took it upon themselves because they knew what they had. I think after my senior year in ’92 (that first Florida State bowl game), they knew what they had and that’s why they were able to make it to the National Championship game the next year and almost make it with that field goal.

We were like this family, man. To put that ‘N’ on your helmet -not only to put that ‘N’ on your helmet- but once you got that Blackshirt you were part of a fraternity for a long time.

Q: Do you recall anything else making a big difference for your teammates?

LB: I would say one of the things that helped was the fact that we went from the traditional, big defense to more of a speed defense, and they started to move guys like myself and Ernie Beler from safety to linebacker. Ed Stewart was another guy. And I think that allowed us to play at the same level as the other teams, like the Florida schools. I think it became more fun, because we were flying around.

Q: Did you buy into that change? Or did you fight it like Ed did?

LB: I was probably more receptive to it, trying to get on the field. I didn’t mind moving closer to the line. They had a plan for me, I guess. The funny part about it, obviously Coach Darlington -he may not remember- we had our differences at that time, but I didn’t care what my position on the depth chart was, I felt I could cover anybody.

Then Coach Samuel told me we were looking at moving some guys up to SAM back, so I made my mind up that I wanted to play offense. Then after that Coach Osborne called me in to talk. And if he was calling you in to talk, you already knew what the outcome was going to be. (laughs) I pretty much told him, ‘Do I have a choice?’ And he said, “Well, we think this would be great for the team.” So I said, ‘Alright.’

Q: So it took his presenting a vision to really make the deal go down, huh?

LB: You know, when you come in you have your own vision. I had my vision, so I really didn’t care about what anyone else said. Until that meeting with Coach Osborne.

I continued with that belief, but I started thinking that I needed to be a lot stronger. I was a quarterback in high school, too, so I thought like an offensive guy. So it took -for me, and this is the honest truth- this is what did it for me one day my freshman year: I saw Jeff Mills, Reggie Cooper, Pat Tyrance and Kenny Walker all together coming out of the North locker room. I saw them guys and I’m like, ‘Damn! All you dudes play defense?!’ They looked so physical and imposing. They were all chiseled.

Q: They were like the Fantastic Four. Superhero-type physiques?

LB: Exactly! At that point I understood I needed to become a little more built, but athletically I didn’t feel like nobody there was that much better of an athlete. You had guys like Curtis Cotton and guys like that, but I never felt I couldn’t stop anybody.

KW: (laughing) I remember for the first day of camp -when they’d have freshmen and newcomers report early- I was playing a little wingback, a lot of route running. (Now you want to talk about a perfectionist? Coach Ron Brown was the best, now. He was one of the best coaches with running, blocking, pass catching, the drills we did as receivers, oh my goodness. He was a very, very good coach). So anyway, I played a lot of receiver as one of the wingbacks. You had Nate Turner and Tyrone Hughes, Danny Pleasant, and then myself, we were all wingbacks at the time, so my first four days it was tough, trying to get used to that style of football.

It was very demanding. It was an eye opener. You’ve got guys that were just as fast and a lot stronger than I was, so it made me realize that I wasn’t as good, wasn’t as great as I thought I was. Coming from a junior college in Kansas, being a first team All-American player in the Jayhawk Conference, Player of the Year unanimous, I thought I’d be ready once I got to the next level. But I tell you what, it was an eye opener. Just very demanding, and there were some big guys out there. I was but 5’8” and 170-175 lbs. You’ve gotta go in there and try to block Pat Tyrance at linebacker? Reggie Cooper at free safety? There wasn’t any turning anything down. I wasn’t scared, but you had to do it. So I had to get in the weight room and get stronger.

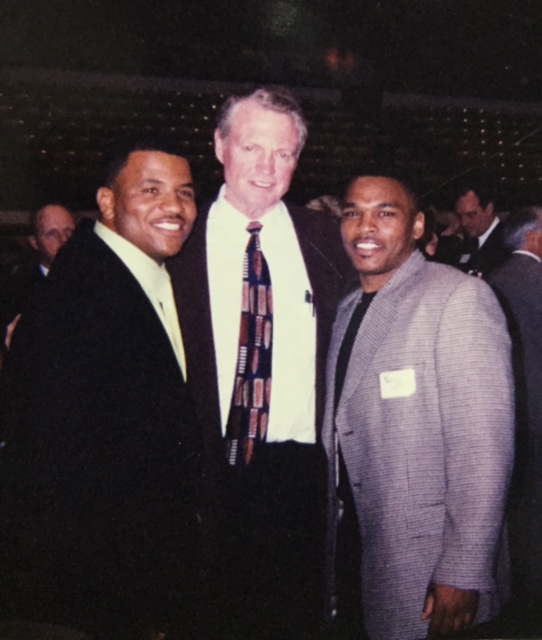

Ernie Beler, Tom Osborne & Kenny Wilhite (Unknown source)

Q: And being converted over to the defense, did it take a while to accustom yourself to delivering the hits instead of receiving them?

LB: In the latter part of my career I did. I think when we got Toby Wright on the team, I think that changed the whole mental state of our defense. Because he’d knock the shit out of you, to put it plainly. So it started to be the game where everybody was trying to knock the living shit out of somebody, and when he came on it showed us it was possible. So those last couple years I became more of a physical guy.

Q: Where do you think Toby’s physicality came from?

LB: Do you know where I think it was instilled? It was his personality and his journey, I’d say, because he had an ACL tear in his knee out of high school and had to go to junior college. And then he had a couple brothers ahead of him who played, too, (the youngest of four brothers who played college ball) so I think he had an idea of how to bring it, you know?

Q: And what about you guys? Were you the first in your family to play college ball?

LB: No, my father was drafted by the Steelers and he played Canadian ball for a time.

To be continued…

Copyright @ 2013 Thermopylae Press. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credits : Unknown Original Sources/Updates Welcomed

Paul Koch