Anatomy of an Era: Kevin Ramaekers, Part 2

Excerpted from Chapter 27, No Place Like Nebraska: Anatomy of an Era, Vol. 1 by Paul Koch

Kevin Ramaekers, Part 2

Q: Was that team cohesiveness/togetherness encouraged by the staff, the coaches?

KR: No, it was just something you did. And you always looked out for each other, whether it be on campus or at the local watering hole or wherever you were, it was just a very tight-knit group. I can’t explain it, the bond and unity that we had was absolutely unbelievable. To get that group of those different personalities together? We came from all over the country, and to get that close? It was like you knew each other since you were in the first grade. Charlie would talk to us in team meetings, “You eleven on the field are like brothers. Every one behind you is a brother to you. You have to look out for each other, take care of each other.” And they’d practice that daily.

And Osborne, in writing our goals up at the beginning of the year, if you look at our Championship rings they said, “Unity, Belief, Respect.” So, unity was #1, then you’ve got to believe in each other, and then you’ve got to respect each other to be one cohesive unit. And we totally were. Absolutely were. Never did you see or hear guys fighting in the huddle. If we were up or we were down, never were people fighting in the huddle. Now, you’d have people come back to the huddle like Trev Alberts or Pat Englebert, or Terry Connealy or John Parrella, and say, ”Pick it up, Ramaekers, that guy was yours. C’mon, that guy got through your hole.” That was it, but it was encouraging. And I don’t know about you, but it hurts a lot more coming from a fellow player than from a coach.

Q: Oh yeah…

KR: When you’ve got Trev Alberts, “That was your guy,” or Mike Anderson or Mike Petko, those linebackers, “You’ve got to squeeze that guard down, he’s all over me.” Then I’m not doing my job. You don’t want to let your guys down. Absolutely not.

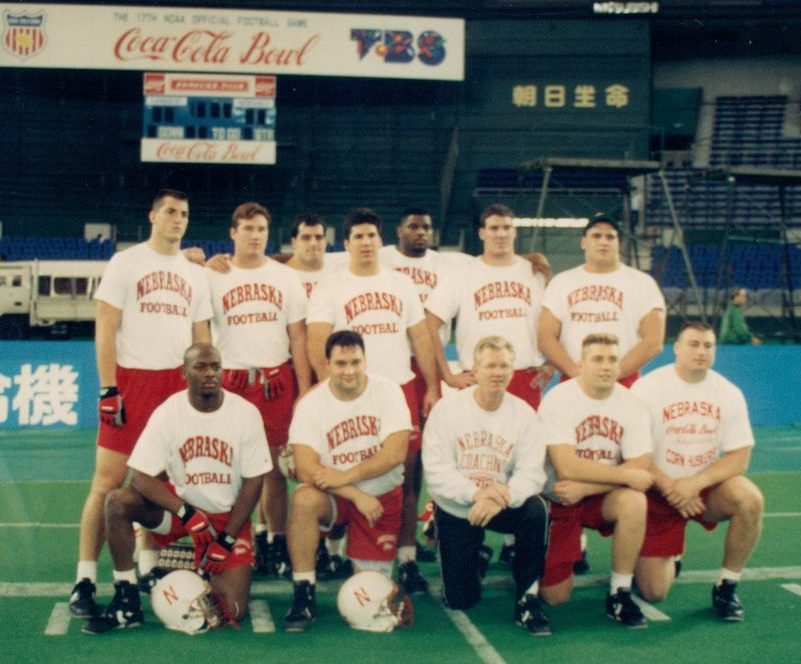

Coca-Cola Bowl, Tokyo: Husker D-Line and Charlie McBride (Unknown source)

Q: What about Coach Osborne?

KR: You know, one thing about Coach Osborne… it was like I said, I came to Nebraska very immature, highly touted and made some really, really immature, bad decisions: got into some fights, got into some trouble downtown- the police and some local students. And Osborne called my parents and I into a meeting on a Sunday morning after I’d been arrested downtown and he basically said, “I’m taking Kevin’s scholarship away. He can’t continue to do this. We’ve given him chances, he keeps messing up.” And he looked at me and he apologized to me. He said, “I’ve failed you. But I promise you one thing, you will graduate from this university and you will be an asset to this community. But I’m telling you right now, you’ll never play on that field again.” I literally sit there -at the time, 290 lbs., 6’ 4”- I’m literally just sobbing in his office. It was the absolute, ultimate wake-up call. It was like, ‘I’m done. I can’t keep doing what I’m doing.’ He telephones me to this day, I get a Christmas card every year, I got a phone call after my parents died, had dinner with him in Chattanooga when he was in town. Just a great guy, just a great guy.

Q: How did you get back on the team after that, Kev?

KR: Well, just proving to him: my grades obviously got better. I worked out hard, came back better, faster from my knee surgery, and just proved to him that ‘I can do it.’ I personally went back to him two or three weeks later and I begged him. I apologized, and he said, ”I’m taking your scholarship away.”

And he called me back a month or two later and asked how committed I was, said he liked what he was seeing, liked what he heard from Boyd and your staff, liked what they were seeing. And he said, “This is your last chance.” And I never, never got called back to his office again (unless there was a player he wanted me to talk to or something came up in Unity Council that he wanted to be aware of).

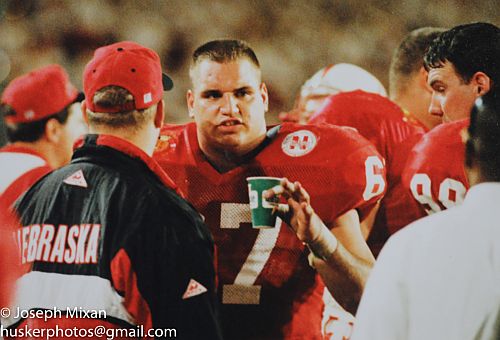

In the trenches vs. the Seminoles. (Joe Mixan photo)

Q: What effect did the Unity Council have?

KR: It was incredible. Now, when I got in trouble -you remember the Unity Council, there were players selected from every position group. There were 8 to 10 guys. We’d meet up in the stadium every Tuesday night after practice and dinner- and I got called in. And I’d get called in normally as a member of the Council, but on this occasion I got called in to sit in “the chair.” Basically it’s a circle of guys and you sit in the chair and you tell the teammates what happened. It was like, ‘I was downtown in a bar. Some guys were ribbing this girl. I told ’em to leave her alone, they started giving me shit. I told them to leave it alone, they didn’t leave ’em alone. The guy pushed me, and I just went off on him. And that’s how it happened.’ Pat Englebert said, “Listen, I love you to death. We’ve been friends since high school,” (since I used to compete against him in track and stuff), and he said, “I’m telling you right now, if you don’t grow up and focus on your schoolwork and focus on the task at hand, they’re gonna let you go. You’re gonna be gone.” Not a lot of guys said anything, because you had Eric Wiegert, you had Mike Croel, but when it came from Pat it was just devastating, because I’d started with the guy the year before! And here I am sitting… I’m a member of the Unity Council, but now I’m in the chair. It was embarrassing.

The deal is, no Unity Council member should ever be in the chair. Those are the guys the coaching staff looks up to, the ones they and the team picked as leaders. So it was extremely humbling, but at the same time it was a blessing in disguise. And I think Coach Osborne obviously knew I had potential. But Paul -at the end of the day?- my problem wasn’t that I was a dumb kid, it was the problem that my ego and my maturity was so far behind everybody else at that age. Because I was so used to being ‘It’, I was the man. It was like, ‘I’ve arrived, I’m here.’ But it was really, ‘You’ve arrived, but you haven’t even started yet.’ I was a nobody.

Q: Any thoughts about any of the other coaches stick out to you, Kevin?

KR: Well, Milt Tenopir and Dan Young had recruited me as an offensive lineman. And Milt Tenopir would always come up to me after a practice or a game and made it a point to tell me how I did or shared things that I could work on after he saw film the following Monday. He’d say, “Do this” or “You had a great game,” just constantly encouraging me. I didn’t even play for the guy. Just always encouraging me. And he was busy enough. He had All-American Jake Young and the guys on the line, and when I redshirted that year I played my ass off against Eric Wiegert and those guys, pushing them. And he’d come up and thank me. He’d tell me, “The guys we faced Saturday afternoon weren’t as good as you. You have a bright future ahead of you.” Even the players would tell me that, “Shit, you’re a lot better than the guy I went against Saturday.” So that was huge compliment, you know? You don’t know intentionally if they were trying to build your confidence up, but just them telling you helped so much.

Q: So now you’re an upperclassman and you’ve gotten past all that immaturity and assumed more of a leadership role on the team. How did you exert your influence on the younger guys?

KR: My deal was, I was constantly a bit of a free spirit, if you’d say that. I was very talkative, very aggressive, very physical, constantly pushing the guys in the weightroom, in summer conditioning. If someone didn’t show up… the next time we’d sit there and bust their balls, really get on them, tried to lead by example. And it’s weird, it was nothing that you practiced or rehearsed for, it would just happen: the work ethic and the aggressiveness on the field.

Now, I would talk shit on the field, you ask anybody. I was an ass on the field and would try to get in guys’ heads, but after practice or in the showers I’d always compliment them, ‘Hey, you had a great practice,’ or ‘You did a good job,’ constantly encouraging the guys around me. The deal is, if I was having fun and I had guys pushing me, it made me work harder. If I felt someone moving up on the depth chart (and I knew how good, you know, Christian Peter was and Jason Peter was), I figured the harder I pushed them the harder it’s gonna make me work, because I don’t want to lose my spot, I don’t want to lose my Blackshirt. And then it was a competition. I wanted to be like Pat Englebert, I wanted to be like John Parrella, and Christian wanted to be like me, and Jason wanted to be like Christian. It was a constant cycle, you know?

Q: So what was your first thought that first day when Charlie said, “You’re joining me on defense”?

KR: I was –honestly?- extremely concerned. Nervous. Because I wasn’t a big fan of defense in high school due to the fact that a lot of times I was double- and triple-teamed, so I wasn’t a standout on defense. But if you’re taking three guys to block someone, that alone is going to leave two guys free or open, so I was just really concerned: ‘I don’t know how to play defense. I know offense. I know how to pull, I know how to pass block.’ But once I got over there and I realized the mentality -and it fit my mentality, the way I was- because when I played the light was on but not everybody was home all the time, you know? (laughs) So I had to play… the best way I could describe it was, “You had to play nuts under control.” You had to play just out of your mind, but you had to control yourself.

Q: That’s a fine line to walk…

KR: Yeah, it was hard. And that’s why I struggled so much early on, because I couldn’t separate leaving the field from walking into The Rail or some other local watering hole.

And that’s really where I struggled. I wanted everyone to know me and know who I was, and I was gonna make a name for myself both on the field and at the local tavern. But one thing -when I got in trouble?- Academic Advisor Dennis LeBlanc told me after I got in trouble, he said, “Listen, I don’t want to see you ever wear another Nebraska t-shirt to class. I don’t want to ever see you wear another Husker sweatshirt to class. You are student.” Because I wanted the attention I’d wear all my Nebraska shit to class, wear a Nebraska sweatshirt to the bars. And if I wasn’t getting attention academically, getting attention playing, physically? I was going to get attention in the bar. Like, how stupid is that, you know?

Q: Was it a little difficult to go incognito thereafter? Actually finding something to wear that didn’t have the Nebraska script on it?

KR: I would basically just go into Christian’s closet or steal Connealy’s clothes. (laughs) That was the joke. Connealy’s mom would tell you, I would go to their house and I’d grab a shirt. I’d take a shirt and wear their clothes. I was your stereotypical dumb jock. I always wore Nebraska shit, and once I was through the transition and put the ego on the back shelf, then I only wore the Nebraska stuff on the field where 80,000 people will see me instead of 100 people at a bar. That made sense.

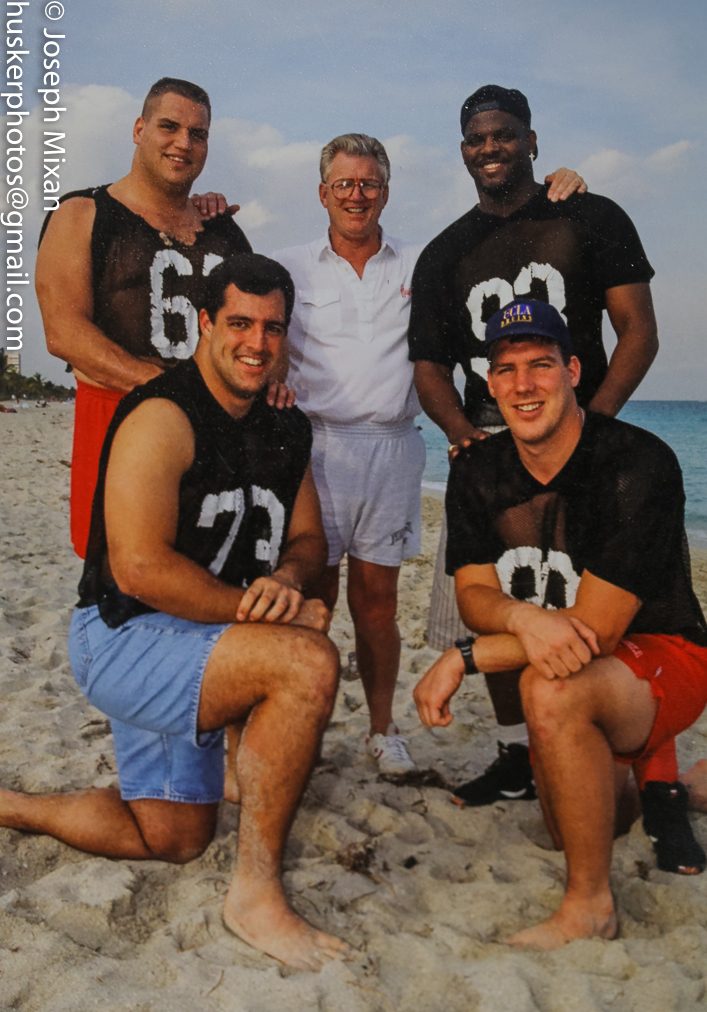

Blackshirts in Miami (Joe Mixan photo)

Q: What about Charlie being a great motivator? What did he say to motivate you?

KR: With Charlie, he was basically all verbal. Very verbal. Now and then he’d grab a couple props, sometimes he’d bring a board with a nail in it to practice. He’d say “If you don’t get off the ball I’m gonna ram this in your ass.” Or he’d take his chewing tobacco (he always chewed Copenhagen), he’d throw it in your face. Charlie was the type of guy, you’d be watching film in meetings and he’d go, “Oh, hell! Look at this!” And it would be a play of me getting hook-blocked. Some guy from Missouri was hooking me and he was like, “You look like a dancing bear! Can you believe it, guys, that we gave a scholarship to a dancing bear?!” And he would just keep going and going and going, to the point where it would be, “Hey Coach, enough. I got it. Enough.” He knew how to motivate each kid differently.

And with me, I responded really well to the nasty, vulgar, verbal abuse. And I wouldn’t even call it verbal abuse. I mean, if we talked to our kids that way, sure, but I knew exactly what his intentions were. I knew after the game, in the locker room he’d come over and give me a hug and kiss me, I just knew that. But Monday through Friday that guy was so far up my ass that you couldn’t even breathe.

Q: So it wasn’t necessarily negative, it was more goading than anything?

KR: Yeah, exactly. He would point it out and let you know, “Hey, you getting ‘hooked’ is unacceptable. You’re better than that.” He’d let you know in front of your teammates so they’d push you too, you know?

And I tell people, ‘When we won, practices were hell the following week.’ When we lost, it was different. It was just kind of the reverse psychology. You would think that when you lose, when you got beat, they’d just tear you down, but they didn’t. They’d still push you -but when we were winning?- they’d be harder on us when we were winning than when we were losing. And we didn’t lose that much, we really didn’t.

Both volumes available on Amazon.com

Q: What, only the Iowa State game your junior year and Florida State game your junior & senior years…

KR: Yeah, we lost that bowl game.

Q: Here’s what I’ve been hearing, Kevin: it seems in ’89, ’90, ’91 there was a little more individualism, not as much closeness in the team?

KR: Yeah, you could see that, too. Guys weren’t as cohesive. You could see that. You remember the training table? It was the same group of guys there at the training table for three years eating together there. It got to the point where Coach Ron Brown and some of the other coaches said, ”Guys, break it up a little bit. Go sit with the freshmen, go sit with the diverse guys.” It was always a group of white guys, so we had to mix it up a little bit. We started doing that and bringing more guys into the circle, and pretty soon it was 6 every week, and then it turned into 8, and then it turned into, hell, we had a whole, huge table of 15-20 guys sitting together eating, you know?

To be continued….

Copyright @ 2013 Thermopylae Press. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credits : Unknown Original Sources/Updates Welcomed

Paul Koch