Anatomy of an Era: Jerry Weber, Athletic Trainer, Part 1

Excerpted from Chapter 43, No Place Like Nebraska: Anatomy of an Era, Vol. 1 by Paul Koch

We have not lost faith, but we have transferred it from God to the medical profession.

-George Bernard Shaw

Bringing it all together for the full-time Athletic Training staff of the 60 & 3 era, we finish with the one man still standing in the training room this very day, recent National Athletic Trainers Association Hall of Famer Jerry Weber. After first hearing from the Gothenburg Dane, Doak Ostergard, some chapters ago, it’s a bit odd that I hadn’t yet touched on the genesis of this wonderfully odd game that has our rapt attention and oftentimes grotesquely skewed affections in the first place: the sport of American Football. I do so because -in a roundabout way- it started with the Danish.

The story goes that after England finally defeated the occupying Dane Army in the year 1042, an Englishman thereafter happened to unearth a Danish soldier’s skull, which he then proceeded to kick around his field just for giggles. Surprisingly, it quickly became all the rage, as other landowners swiftly began digging up their own “headballs,” as they became known.

Soon though, the rigidity of a skeletonized human melon became too painful for the delicate feet of the local populace, so they quickly reverted to the use of inflated cow bladders instead. The next great advance was to place one of these “footballs” half the distance between two neighboring towns, whereafter the townfolk to first kick the ball into the others’ town square was declared the winner.

Flash forward then, to 1869, where a mutated version of the sport a little closer to present day football first took place between Rutgers and Princeton. I’m not sure what the final score was, or who even won that contest, but suffice to say, it caught on like a prairie fire.

Almost exactly 100 years to the day of that first game, a son of the Western Nebraska grasslands joined the staff as a greenhorn trainer: our very own Jerry Weber. Let’s hear from our man, “Webex,” a training machine spanning a career of “headballs” and the calamity they’ve wrought on young mens’ bodies and spirits…

Notable quote #1:

“It isn’t just the X’s and O’s and getting the A’s and B’s. There’s a spiritual element to it. There’s an element of leadership and mentorship.”

Jerry Weber

Question: So tell me, Jerry, first off: where did you grow up?

Jerry Weber: Sidney, Nebraska.

Q: Out west. Past Ole’s Big Game Bar in Paxton…?

JW: Even way past that. About a hundred miles west of there. A long way from Lincoln, Nebraska.

Q: So how did you end up joining the staff there in Lincoln?

JW: Well, I was not athletic at all in high school; I was not an athlete. One of the coaches, Harold Chaffee (who ended up being the Wesleyan head coach for years there), and Duke Osterday, they asked me if I’d like to be a student manager in high school. And there was a company in Olathe, Kansas called Kramers Sports Medicine, they had a student course you could take. They’d send you the stuff, you’d study it and you’d take a test: how to tape an athlete, how to take care of wounds and injuries and whatever. Just a very rudimentary level. And I took that course.

And then Tom Ernst, who was the football coach after that (He had played down here at the University. He was from Columbus, Nebraska, State Athlete of the Year at one time), he knew Paul Schneider and George Sullivan and called and said, “I’ve got a kid I think would be good to work with you guys.” So Paul said, “Send him down here.” That would have been the summer of 1969.

I stopped in and met Paul. Paul was doing basketball camp and it was hot in the Coliseum, and he was sweaty and he said, “Yeah, I think you’ll be fine. Be here at such and such a date.” And that was it. (laughs) So I started as a student athletic trainer here in 1969 and was here 5 years as an undergrad, and George and Roger Long were both Athletic Trainers and Physical Therapists. At one point in my early career I thought I wanted to be a doctor, but after the time there and being a training room rat and hanging out with those guys and seeing this was going to become a passion of mine, I decided to go to Physical Therapy school, because I saw that as the best pathway to eventually get a job here. So I did that and was in the Med Center PT program and graduated in ’76 and went to Western Illinois University for a year. And every year Duke LaRue would bring in a young PT to be the staff physical therapist in the Health Center in the mornings, and then at 4 p.m. you’d come to the athletics and work with the kids. And the thing that was nice, they paid you a salary. And then they also paid for me to go to school and get my Masters.

So it was ideal: I worked with football, traveled with football, wrestling, track and baseball… traveled quite a bit with baseball. Then Paul Schnieder, who was a lifelong smoker, he got emphysema and then he moved over to the Devaney Sports Center with Jim Ross, so they asked me to come back. And I’ve been around here for forty years. So my career path was very fortunate.

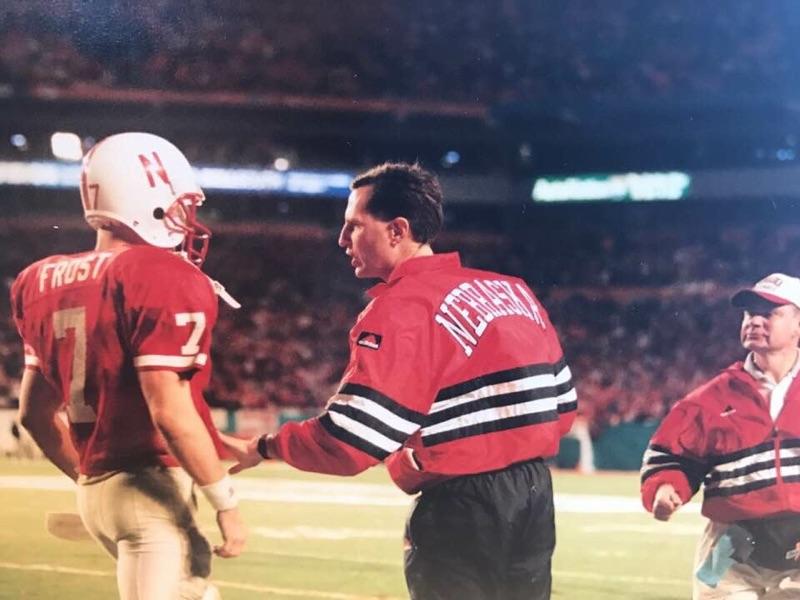

Jerry Weber, far right (Unknown Source)

Q: What’s your title right now, Jerry?

JW: I’m the Head Athletic Trainer, Physical Therapist and Associate Athletic Director for Athletic Medicine.

Q: Wow, sounds like you have a lot on your plate…

JW: Yeah, I do, but it’s kind of the point where we have demands on athletes all year long now. And the size of the program with the teams and sports we have? We have a fairly large staff. And I’ve been able to hire really, really good people. And that’s the key to any success, hiring people to do a good job and make you look good.

We have a full-time football staff, which we started in the mid-’90’s that we kind of organized when George retired. And I became Head Athletic Trainer and we decided to hire a full-time head football athletic trainer, because the demands of that sport require you to devote your whole time to that. You can’t do that if you’re also going to be looking over and seeing how the other teams are doing. So we split up those duties and it’s worked out really well. Some athletic trainers are full-time with certain sports, and I oversee them and work with a number of sports, yet.

Q: Was gymnastics always something you did?

JW: Yes, men’s gymnastics, and of course, women’s gymnastics, because when I got here in 1977 most of the sports like football had priority, and basketball, and we had maybe a part-time female assistant and that all grew when I first came here. The model around the country was the head athletic trainer and then an assistant. And the head ATC was in charge of football year long, the assistant worked football yearlong until the bowl game, after the bowl game he traveled with men’s basketball. So we did that, and then we had students with the other sports.

So I did that for my first four or five years until the demands of rehab just got to be too much. We had a good student, our first graduate assistant in Jack Nickolite, we hired him as men’s basketball athletic trainer. So that’s kind of grown along those lines ever since.

Q: Wow, amazing how that’s changed from even a dozen years ago. And you‘ve been there a full forty years now in some capacity?

JW: Well, forty years as of yesterday. You just take some personal pride and accomplishment to be in one place that long, and hopefully I’ve contributed. But you just don’t think about it, you know? It’s really unusual for somebody in my profession. I’m a dinosaur, there are very few young people in their thirties or forties that will have a career like I’ve had at one place. You get burned out or bounced around, you just can’t handle the stress, and sometimes you go into a different profession or do it part-time. So it’s been quite a run.

Q: Now, most of the fans reading this may not realize how time-intensive being an athletic trainer is. What has kept you going strong?

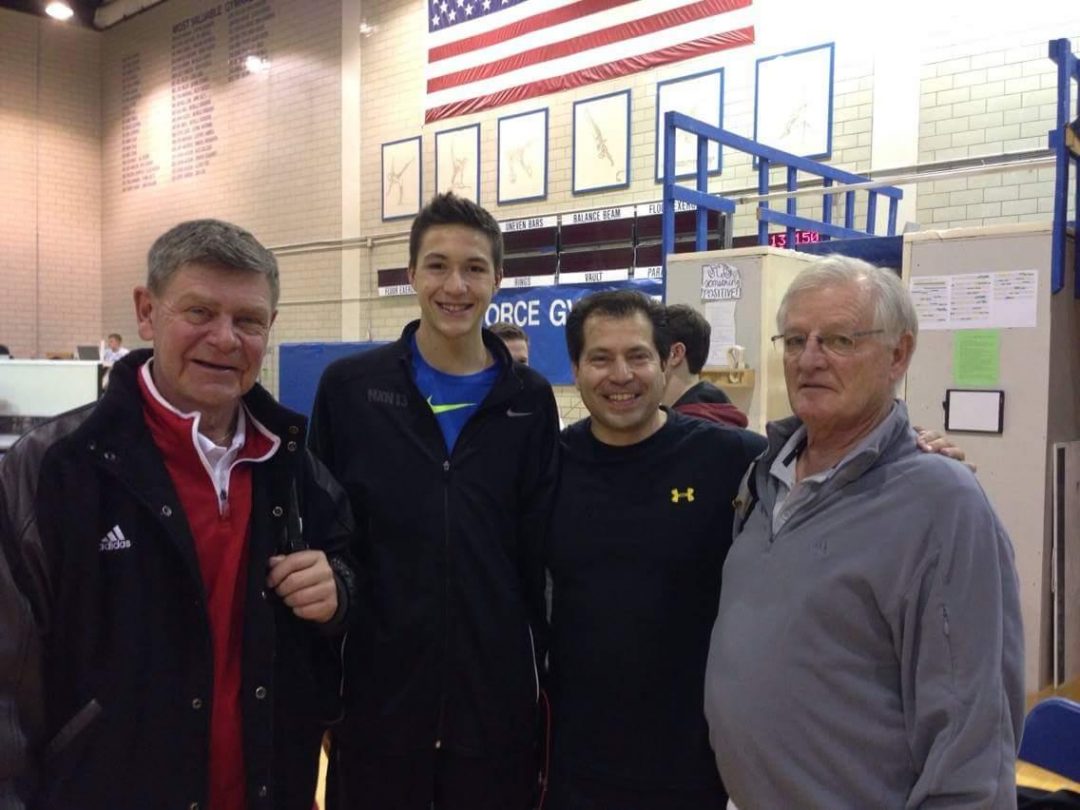

Jerry Weber, Husker All-American Ted Dimas with son, Coach Francis Allen (Unknown Source)

JW: Just the day-to-day interaction with the athletes. We’re in a position where we see a young man or young woman, 17 or 18 years old, and a lot are very mature, a lot of them aren’t. A lot just don’t have a lot of life down yet, you see them grow from a boy or girl into a man or woman those four, five years they’re here. It’s that maturation process and the interactions. Some people ask me, “Isn’t it boring doing the same thing every day, taping ankles over and over, etc.?” And I don’t think of it that way. Every day is a challenge. You never know what’s going to come up. You think you’re cruising along and all of a sudden something comes up that you haven’t seen or somebody else hasn’t seen, and maybe you have the answer. So it’s just the day to day interaction with the athletes that I enjoy.

Q: Now, my focus for this book is the arc the program took in that 1990’s era. And speaking of that, who stands out to you as far as personalities?

JW: Well, there were an awful lot of them, obviously. I wish I had the media guides from those years. I have people come up to me all the time and they go, “Hey Jerry, it’s good to see you, you’re looking great. Remember me?” And I go ‘No.’ (laughs) I say, ‘Okay, you’ve got to help me. When did you graduate?’ I’ll have to think about who else was around then, because after a while it all runs together.

But some kids you really remember from that era. It sounds weird, but Byron Bennett was one really special kid. Byron was a kicker — and I hate to say this, and a few of them aren’t, but most kickers are a little goofy, you know? (laughs) Them, and pole vaulters and divers. They have a specific talent, they’re individualist and they’re really on an island. And you have to understand them, because often times you’re either gonna be the hero or the goat. And Byron had all those things happen to him. As a freshman or sophomore at practice with that old Astroturf they were practicing field goals or extra points and there was a fumbled placement. He picked it up and scrambled for the goal line, turned his knee, and he tears his ACL. So here you go: a young kicker trying to prove his worth and tears his ACL, so he had to go through all that rehab. So I got to know Byron very well after that. And he came back and became a very successful kicker for us, and of course, he’s unfortunately known for the miss at the Florida State game…

Q: Among the many ‘makes’…

JW: Yeah. Many, many makes. He probably saved a bunch of games, but a lot of people remember Byron for missing that field goal, and it’s unfortunate. So kids like that stand out. When we played at the Cotton Bowl a few years ago he came down to the field at a practice and he came up and said hi, and we even corresponded for a year or so after that.

Both volumes available on Amazon.com

You get little notes from some kids sometimes. They say, “I want you to know you were special to me, etc.” And Byron did that. He was special. Another kid who was special to a lot of people, and me in particular, was Brook Berringer: his personality and character. He was always kind of an underdog guy. I always kind of hung with the underdogs a little bit. Not that you paid them any more attention, but you appreciated them a little more. Kind of like the walk-ons. But he was always in the shadow of the other quarterbacks he played with. He was hurt, had the lung injuries, and just ended up fighting back through those chest injuries and was a key element to getting us to that ’95 Orange Bowl. That whole time, just a quality kid who never complained about anything, was really well grounded, had lost his father early in life. So some of those kids.

There were so many kids who, as you get older, you tend to be a bit of a father figure for some kids, and I think I helped fill that role a little bit; just somebody to confide to and ask questions about things. And you feel good about the answers that you give those kids, because you’d like to think that you’re helping them grow up. But Brook was really special: he’d be respectful, had a great work ethic. And his legend grew when he was killed in the plane wreck. That was a devastating time for everybody. It was a rough time.

I can’t remember when Jake Young played, but he was a special player, too. Great athlete, really smart, always a great sense of humor. A smart ass, basically. You get close to kids because you spend more time with them when they get injured; sometimes 3 hours a day when they get injured, so you really get a chance to know them more. Some kids, for some reason, you turn around and they’re sitting in your office, and you say, ‘What are you doing here?’ And they say, “I just wanted to stop by and see what’s going on.” And they want to get to know you better, which is fine, and you become their ‘guy,’ which is fine. And that’s another thing that’s special about this profession. Because a lot of times you can’t get that close to people and they to you, so it’s pretty special when you’re here all day long. They appreciate when you’re gonna be here and available to them all the time.

Q: Matt Turman said that you were his ‘guy’…

JW: We all had our guys, and we still do. Regardless of who is on staff or if you come in and out of football. That’s what I do now, I’m helping these guys with some things but I don’t make football decisions. I take guys and, even though I’m not the head football guy, they vegetate towards you…(laughs) … gravitate towards you. And Matt was one of those who did that. There are a lot of them.

Matt was a good guy. I remember he got hurt, he was just easy to get along with. And you had no expectation when he got here: undersized kid from a small town in Nebraska. Good athlete. Not a great athlete, but a smart kid. And especially when Brook and Tommie got hurt, that Kansas State game? He really did a great job. It’s good to hear some of those kids remember you and are kind enough to mention you once in a while.

Q: Well, a lot of them say that you were really special to the whole organization and that you were one of the wizards behind the curtain…

JW: You know, to a certain extent that’s a good way to put it. We are behind the curtain. We’re behind the scenes and that’s fine, we’re not hired to be out there. And we do some things that you weren’t specifically hired to do for them, but you do, because we care for them. And if you’re an athletic trainer or a strength coach or whatever kind of advisor. And often something special clicks, and it’s my job to make sure I do see that happens a bit.

I’m sure there are a lot of people in this profession that don’t want that relationship. They either don’t have the personality or are scared by it, or some just embrace it. But I think you have to as a part of this profession. I tell our young student assistants that, ‘Hey, you have to treat our athletes better than that. You don’t have to be their best buddy and their comrade and feeling sorry for them, but you have to be their friend.’ And a lot of people, I don’t think they get that sometimes. And, of course, that’s another reason they don’t stay in this profession. They need to be some kind of an ally to the kids.

Q: That being said, is there something about being a Nebraskan which speaks to that? Was there something to that when Coach Osborne was the head coach?

JW: I think it goes back all the way to Coach Devaney. Seriously, you look at his ethic when he came in and developed a culture here. It was one of the underdogs that all of a sudden became the top dog, because Nebraska certainly was the underdog in the early ’40’s and ’50’s and ’60’s until he got here. He created a sense of wellness for the state, and I think everybody in the state took hold of that. It became pretty apparent that was what was expected. And I think your Midwest attitudes -conservative and family values- they are really important. I think it’s really easy for them to wash over to this system, and certainly Coach Osborne exemplified that.

To be continued….

Copyright @ 2013 Thermopylae Press. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credits : Unknown Original Sources/Updates Welcomed

Paul Koch