Anatomy of an Era: Jason Peter, Part 1

Excerpted from Chapter 77, No Place Like Nebraska: Anatomy of an Era, Vol. 2 by Paul Koch

Nearly every boy can run, jump, swim, play a passable game of tennis, or hit a golf ball, but not every boy can play football. The game calls for an extraordinary amount of physical courage and combativeness…demands a certain type of intelligence, or if not intelligence, then adaptability to regimentation and the formation of habits.

-Paul Gallico, Last Stronghold of Hypocrisy, Farewell to Sport

In the Cornhusker tradition, it’s about time we hold a hand high in the air and turn the thumb inward to the palm, signifying with four fingers raised that we’re now in the fourth and final quarter of our literary contest…our journey…our man-by-man search…our quest to pin down and extract crucial tidbits about that great era. That late-game’s hand gesture always served as a reminder to the Nebraska elevens that this was what all the extra offseason work was for, that this was the moment where men played like tireless gods and losers devolved into tired cowards, where the will to win, to dominate, mattered more than anything and everything.

It also signaled to the opponent that, in the famous shout of American patriot John Paul Jones, “I have not yet begun to fight!” It meant the opponent, much to his chagrin, was to experience the same Nebraska effort as they had the first three quarters. And then some.

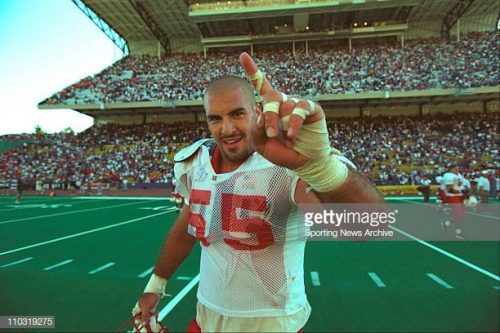

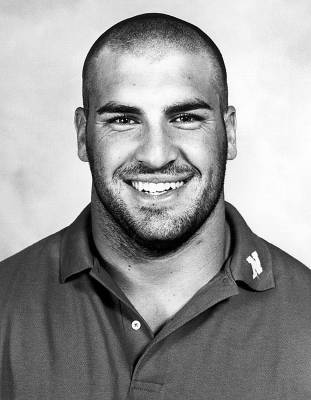

We open our final quarter’s salvo with a man who’s lived a lifetime and then some: Jason Peter. No doubt you’ve cheered at his exploits and maybe even jeered at his travails, but this toughest of Jersey jocks is a survivor, a fighter, a scratcher and a biter. Author of the best-selling personal memoir Hero of the Underground, Jason seldom minces words. Like his father’s restaurant in New Jersey, let’s partake of the fine morsels of his five-star experience as we count down the clock to the final, inevitable summation.

Notable quote #1:

“It all starts with the in-state people, whether you’re talking about the fans or the in-state walk-on kids. These are people who have an immense amount of love and appreciation for the program, and for some it’s a dream to be able to go down there and be part of that program. And for others, to sit in the stadium and watch their team play is a dream itself. When you have people like that supporting your program it’s hard to do anything less than give everything you’ve got.”

Jason Peter

Scholarship recruit, Defensive Tackle, locust, New Jersey (Middletown South)

Where are they now? Lincoln, Nebraska, Philanthropy

Question: Hey Jason, it’s been a long time, man. I’m talking to a father, a former pro football player, and oh, by the way, a best-selling author. It’s been a while.

Jason Peter: Yes, it has.

Q: In my reading your book, Hero of the Underground, you detailed how you essentially gray-shirted yourself and went to Milford Academy in Connecticut before coming to Nebraska. Can you share more about that?

JP: Yeah, I played two years at Middletown South in New Jersey and I was young for my class -sixteen years old starting my class off- so when I finished playing my senior year I just didn’t have the amount of attention recruiting-wise that I wanted.

I wanted a Division I scholarship, and a coach from Miami by the name of Art Kehoe -an offensive line coach there- told my parents about a school in Connecticut where I could go and redo my senior year and play football and see what happens recruiting-wise when I left there.

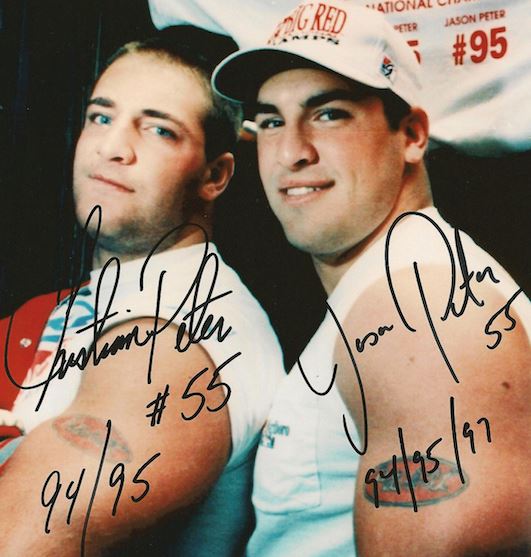

And when I left there after my senior year I could pretty much write my own ticket as to where I wanted to play, getting a lot of scholarship offers from everybody. I narrowed it down to five, and to say that having Christian here at Nebraska play a role as to where to go would be an understatement. There was a comfort level when I came out on my recruiting trip, and just having Christian there and already knowing some of the guys that were on the team was pretty comforting for a 17-year-old kid. So it was pretty easy for me to sign my name on that bottom line, and I’ve never regretted it for a second.

Q: I have to ask, how did your folks end up talking to Coach Kehoe from Miami U?

JP: Well, they were recruiting me a little bit coming out of Middletown South; both Nebraska and Miami both had offered me invitations to walk on, kind of one of those ‘preferred walk-on’ type deals. But he knew that I wasn’t really interested in that and I guess he figured that maybe in a year after being at Milford that maybe they’d have another shot. And that’s one of the schools I did take a recruiting trip to, but in the end I think I just wanted to come to Nebraska.

Q: Anything in particular make you think twice about Coral Gables?

JP: It was a school I really liked, and obviously the football tradition there was second to none, but I think it had more to do with all the extras that Nebraska had to offer: with my brother being here and wanting the opportunity to play next to one another, side by side, which we were able to do my sophomore year in ’95. It wasn’t really the negative things about Miami, it was just that there were so many positives here at Nebraska.

Q: Other than knowing Christian, who were some of the other guys you were pretty well-acquainted with when you stepped onto campus?

JP: Oh, Kevin Ramaekers was Christian’s roommate. And the summer before I went to Milford Academy I came out and was able to kind of work out and do some of the stuff during the summer, and John Parrella was a guy that was still there and working out. Jon Pedersen and Jason Pesterfield and Terry Connealy, they were Christian’s closest friends, so I was able to spend some time with those guys, as well.

Q: I’ve been told that Ramaekers and Parrella provided a type of leadership that expressed what being a Husker truly meant. Did anything rub off on you?

JP: Sure. When I first got here to Nebraska I wanted to be Kevin Ramaekers.

Q: Oh, man! (laughs)

JP: Yeah. He was the guy who was the starter at defensive tackle, so naturally I just looked up to him and watched the way that he went about his business. Kevin, an in-state guy and seeing what the program meant to him, it was just natural that that was the way I needed to approach it. And Kevin’s having to overcome a major knee injury? He was a guy who was a starter as a sophomore and then blows his knee out, and really battled back to being a team leader his senior year. The guy just had an extreme work ethic. He just never did anything half-assed, and everything was all or nothing. That was a mentality that most of the guys had in going about their daily activities. It just so happened that Kevin was a guy who played the same position as me, so I spent some time with him studying how he played the game. He was nothing but a great role model for me.

Q: Speaking to that work ethic, did you originally have it? Did you bring an extent of that with you or was it learned from guys like Kevin?

JP: I had some degree of it being raised by my parents. My father was a strict immigrant from Germany and was of the same mentality where if you were going to do something you were going to put the maximum effort in and be completely dedicated to it. That’s the environment I was raised in. When I got to Nebraska I think it was taken to another level. I think it was great, because for me the foundation was laid, but when you talk about playing on teams where you win three national championships? I think it’s taken to another level.

When you learn stuff from guys like Ramaekers and Parrella and Christian and the guys that were there like Trev Alberts and Connealy… when you have a bunch of guys who continue to push each other and hold one another accountable what you end up with is successful football teams. Anything in life -business or you name it- when you hold one another accountable that’s the biggest plus that you can have in a business or on a team.

Q: You mention your father, that you were from a German immigrant family. How did that come about?

JP: He was from Germany and came to the states when he was 25; one of those rags-to-riches-type stories, worked extremely hard in the restaurant business, and one day he opened his own restaurant with his brother and eventually it’s a Five Star restaurant. Rated one of the best restaurants in New Jersey. A lot of hard work.

Q: Now, my knowledge of New Jersey is limited to Fairlawn, Paramus, Bergen and that whole northern area…

JP: We’re from central Jersey, right on the shore.

Q: So you’re first-generation American. And how about your mom?

JP: My mom is from Michigan, actually.

Q: So she married a crazy German, huh?! I only say that because I’m a fourth generation crazy German. (laughs) You were talking about guys holding each other accountable. What was done when guys were dragging ass?

JP: It could be a verbal onslaught, it could be a physical-type deal. You’d get embarrassed in front of your peers, and nothing’s worse than that. If somebody was slacking off in summer running drills or whatever it may be, like practice -and you weren’t giving full effort?- you were gonna get called out. And that was an environment that was established when I got to Nebraska and that was something that I tried to carry on through my senior year.

Q: Do you recall the first time you ever got called out? Or did you ever get called out?

JP: I tried not to get called out. I think that was the best thing to do and I think that’s why we were able to be so successful, because we had guys that didn’t want to get called out.

Certainly there were guys who would stretch the limits, guys who sometimes thought, “I’m not playing a key role in this game or I’m being redshirted and that means I have a ticket to easy street,” and that was usually the fastest ticket you could get to being embarrassed. It did happen, but it didn’t happen often.

Q: But it happened often enough to make an impression on whomever was around at that time?

JP: Yes.

Q: I read an interview you gave when your book came out and you spoke of taking responsibility for yourselves, taking ownership of the program. Can you talk a little more about that?

JP: We tried to handle things ourselves. If it got to Coach Osborne or any of the assistant coaches then it got too far. And if it got past us, we didn’t do our job. You know, it’s one thing when a coach tells you to do something but it’s something completely different when one of your peers does. Not to say it doesn’t mean a lot when it comes from a coach, but when it’s a classmate or a teammate who says you’re not going hard enough or fast enough, that kind of digs deep. It hurts when it gets to that point.

We tried to handle as much as we could within the team, amongst the players, and certainly there were some issues that got to the coaches and we needed their take, their input, their advice on certain things, but the team kind of regulated itself. That’s a position I think most coaches would like their team to get to. It’s where the team leaders and the seniors and upperclassmen kind of handle all those little things.

Q: Let the coaches coach, huh?

JP: Right. Exactly.

Q: Speaking of letting coaches coach, I spoke to Charlie a few weeks ago. What were your first impressions of Charlie McBride?

JP: I was scared to death of him. (laughs) I’d sit in the back of the meeting room with the rest of the freshmen and just sweat bullets hoping that he wasn’t going to call me out today or say I did a bad job or a poor job of playing a certain technique, or if he didn’t think I was playing well enough on a certain play. He was a motivating force, to say the least. You wanted to please him. Like a father figure, you wanted to please him.

Q: I hear Mrs. McBride recently said that he misses you guys so much…

JP: Yeah, I stay in contact with him as much as I can, try to talk to him at least once or twice a week. We all miss one another. You get to the point where you’re not in the locker room anymore and you miss that camaraderie, you miss that brotherhood. Since organized sports has been over in my life, that’s probably the thing I miss most.

Q: How do you then fill that void?

JP: It‘s tough. When I was living in California I was coaching up there in Orange County. And obviously it’s a different role from being a player, but you’re still in that locker room environment. And now and then I play a little pick-up hockey here and there. That’s about the closest thing I can get to that locker room feeling.

Q: I saw a short video clip of the time you were coaching with that Huntington Beach team. I saw you walking off the field with your arm around a kid’s neck and instantly thought to myself, ‘That’s a mirror image of Charlie McBride!’

JP: Yeah, that was always his motto, “If you stand there and chew a guy out and tell him ‘you didn’t do good enough’ on one play, then you’ve got to be man enough to walk off the field and hug his neck and tell him you love him and you want the best for him.” That’s what Coach McBride did. He’s probably the most influential coach in my life, not just as the defensive coordinator, but also as my position coach. So I spent morning, noon and night with him. He taught me everything I know.

I remember being in the NFL my first year and I‘d be on the phone with him once or twice a week trying to have some question answered, ‘If this happens, what do I do?’ I just felt like I wasn’t getting it from the coach I had at the time and I knew that Coach McBride would answer my questions. He means the world to me, not just as a coach but as a human being. He really was the father-figure-type for a kid who was a couple thousand miles away from home.

Q: Wow, Charlie and his Copenhagen and that stick he called ‘The Motivator.’ Did you ever meet up with that paddle?

JP: “Charlie’s Ass Beater,” that’s what it was called. No, I never did. (laughs)

Available on Amazon.com

Q: And speaking of coaches, what about Coach Osborne?

JP: Words can’t express what the guy meant to me and to everybody. I never came across anybody that had a bad thing to say about him. Obviously, the complete opposite of what Coach McBride was. But I think that’s where it worked, I think. They both knew their role and they both had their own personality and they both respected one another. It’s something where it’s still …a week or so ago I was at the stadium in (Tom Osborne’s) office and just talking about life and different opportunities, and he’s always offering if he can help. Anything you ever need, he’s always been there for me. A great guy, a guy you try to live your life like he did. I always said if I could live it just a quarter of the way -with his beliefs and values- I think I’d be living my life pretty well.

Q: It seems like he is always encouraging and pointing others to a hope-filled future…

JP: Yeah, like I said, he was a big part of my time out there. And when Grant and I both had the opportunity to leave after our junior years… if there was a different head coach there, maybe we would have done something else. But we wanted to go out as national champs, to send Coach Osborne out as a national champion coach, and I can’t definitely say we would have done that for anyone else.

Q: Jason, I gave Coach Osborne a ride to go visit Lawrence in jail here in San Diego when the team was playing here for the bowl game, and I asked him, ‘Coach, I have to know, what was the biggest surprise of your career?’ And he said that it was you and Grant coming back for your senior year. That was the biggest surprise for him…

JP: Really? He tells the story where he didn’t think we were gonna come back, that we were gonna leave. He sat in front of us and said, “I’m not going to tell you guys anything different so you come back. You’re both pretty much locked to go in the first round, and I wouldn’t blame you if you did.” I think he was shocked when he said, “Well, you guys can go home and think about it and let me know,” and we let him know in about ten seconds we were coming back.

Q: Both of you guys were in the same meeting?

JP: Yeah.

Q: Did he show any visible reaction to your answer?

JP: He had a smile on his face when we told him we were coming back. It was Unfinished Business for us. We felt we kind of let ’96 get away from us. We thought that was a pretty good team and we felt like we probably should have won a national championship that year and just kind of stumbled there at the end. So we didn’t want to go out that way.

Q: And let me ask you, did you guys have a slogan for that year in ’97?

JP: Oh geez, I couldn’t tell you exactly what it was. There were so many: Refuse to Lose, Unfinished Business… I could probably find a t-shirt downstairs with something on it. (laughs)

Q: A t-shirt that probably doesn’t even fit you anymore?

JP: Yeah, I know. About ten times too big.

Q: Any other coaches from that time who stick out to you as to what they brought to the whole organization itself? A particular niche, possessing something special?

JP: Coach Solich always was a special coach for Christian and I. He recruited us and he was the coach that I probably had, besides Coach McBride, the closest relationship with. He was friends with my parents and was always in contact with them and he was just always there.

I tell the story: one of my biggest, most difficult days I’ve ever had to deal with was a couple years after I was finished playing the NFL and Coach Solich had called me and wanted to know if I was interested in coming back and coaching at Nebraska. And I had to tell him I was in rehab. That was the first time I was in rehab. I still, to this day, it kills me and is one of my big regrets, but I had to tell him that: ‘I can’t take care of myself, let alone be around 17, 18, 19-year-old kids.’ But he was always kind of looking out for me, and Christian, as well.

And Coach Solich is a guy who was intense. And you watched the way he went about his business, a guy that you talk about getting players to play for him, as well. Unbelievable, the players that he turned out. You look at some of the running backs out there these days, the five-star prima donnas. I just think to myself, ‘If Coach Solich could have gotten ahold of some of these kids he actually would have made players out of them and made men out of them.’

Q: In that vein, do you recall any methods to his madness, how he churned out such quality backs?

JP: I think he still had that twenty-one year old fullback for Nebraska living inside of him, a guy who played for the University. He loved the University. And still, in my eyes and in my book, it’s still one of the biggest injustices in the world what happened to Coach in 2003. He should still realistically be the head coach. Bo Pelini said that his first year back when he was named the head coach here at Nebraska. That’s the truth. And it’s a shame, because he loved the program and he would have done anything for it. When you have guys like that around the program and you see the way they respect the program and how much it means to them, it’s hard not to be taken by that and apply it to yourself.

Copyright @ 2013 Thermopylae Press. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credits : Unknown Original Sources/Updates Welcomed

Author assumes no responsibility for interviewee errors or misstatements of fact.