Anatomy of an Era: Coach Tony Samuel

Excerpted from Chapter 21, No Place Like Nebraska: Anatomy of an Era, Vol. 1 by Paul Koch

“Coaches have to watch for what they don’t want to see and listen to what they don’t want to hear.” – John Madden

The second man from the coaching staff to respond to my query, I corralled Tony Samuel on his home phone early one offseason morning in Cape Girardeau, Missouri. This was prior to his leading the Southeast Missouri State University Redhawks to their first winning season and playoff appearance in a decade and being honored as winner of the prestigious Eddie Robinson Award as the Football Championship Subdivision National Coach of the Year. A former Nebraska player himself, the man known for his coolness and confidence has taken many of the ’90’s lessons and applies them in the present day. I’m excited to hear what he has to share. Buckle up and listen up: you’re about to get an education.

Notable quote #1:

“I always thought our edge had a lot to do with special teams, which had a lot to do with depth, which, to me, went directly back to the walk-on program.”

Tony Samuel

Where are they now: University of Nevada-Las Vegas, Defensive Line Coach

Question: What do you recall about the first day you stepped on campus as a student, Tony? Any lasting impressions?

Tony Samuel: It was cold. It was a recruiting trip. And then the first time I came back was early August for fall camp that first year, and then it was very hot. Out at the old airport where you walk off the plane into the outdoors you felt the air blowing hot, and that was the first time I ever felt hot air blowing on me. (laughs)

It was very different coming out of that environment where I grew up in Jersey City. As far as the original culture there? First you had the fact that I’d never lived in a dorm before, that was different. Doing things with the whole team and eating at the training table, that was unique. It was all completely different. Life was a little slower paced, a lot of family-type people. Coming out of high school living in one world and all of a sudden you show up and its entirely different. And then you show up for camp, and then you realize how big some of these guys really were. Back in the ’70’s you wore tight-fighting clothes, so you could tell when a guy was pretty well put-together. (laughs)

Q: So you returned as a full-time coach in ’86. What role did you play on the staff, rush ends from the start?

TS: Well, we called it (that’s the part that really became confusing to a lot of people), we called it a Defensive End back then, but they were really, truly Outside Linebackers. Because we ran a 50 defense and an Eagle defense, and later we switched to the 4-3, then they were truly Rush Ends/Defensive Ends.

Q: If I recall, did they change the name to Outside Linebacker when the Butkus Award first started?

TS: Well, we had Rush Ends, and I coached Rush Ends and outside SAM backers, which was the Outside Linebacker. We went from, if I remember correctly, from Defensive End to Outside Linebacker, then we switched to Rush End.

Q: Different names but the same position, regardless?

TS: No, when I first got there it was a different defense. The Travis Hills, the Trev Alberts, they were right in the transition period. They were true Outside Linebackers.

When I played, I never put my hand on the ground, I was a standup-type football player. And so was Broderick Thomas in the late ’80’s, for the most part. After that transition we put the hand on the ground when we played our nickel defense, which started to become popular, if you remember, around the country. That started getting popular and we put our nickel defense with a four-man front with all four of the men’s hands on the ground. Those guys were then playing both Outside Linebacker and Defensive End depending on what package we had on the field.

Q: I bet that kept some offenses guessing.

TS: It was our nickel defense where on passing situations we’d put that in, and after the years it finally just became our 4-3 defense (after we had a run against the University of Washington, because they had a real similar defense that we started to run). And you know coaches are copycats, and we went to the 4-3. And then we went to what we called a Bubble Defense, which was another way of attacking, which got its start at the University of Arizona. More and more, as the years go on, it’s very multiple defenses, you know? Like right now you see people talk about the 3-4 defense; in my head that’s the 50 defense.

Q: Old wine in a new bottles?

TS: Yeah, a few differences, of course, depending on how you look at it. 34 has 3 down linemen, and the 50 defense has 3 down linemen, depends on the terminology.

Q: What was the coaching staff dynamic?

TS: Charlie (McBride) had gotten there in about ’77, my senior year. He coached me, and George (Darlington) was my position coach.

Q: Did you always see yourself getting into coaching?

TS: When I was done playing I was actually thinking of teaching. I knew I could do it, and then I found out I had a chance to be pretty good at it. I really liked working with players, helping them overcome the speed bumps and the hurdles that you have to go through. I hadn’t planned on being a coach, but once I started doing it I knew that’s what I wanted to do.

Q: Now Tony, you’ve coached some great players. What might those hurdles be?

TS: First and foremost, you get to the university and you have the differences, some people say ‘culture’ and all of that, you’re in the dorm and all of that, the freedom, responsibility, dealing with being a public figure, going to school, and just the general issues of needing someone to talk to. So many things before you even start talking about understanding how important it is to learn and fine-tune all these different football techniques. Some of these kids coming out of high school, they’re so good they can rely on those physical attributes and gifts.

Q: Who sticks out most among those under your tutelage? Who made the biggest strides?

TS: I think they all did. I remember when I came back in ’86 in the spring, Broderick was a sophomore (because he never redshirted) and he was very, very willing, but he needed to…he was a defensive lineman in high school in the interior, but he was a guy where we worked together and he was very willing to learn.

Q: He had a good motor?

TS: He had a great motor, but by far there were others. The only guy that came close to being ready to play in my career there was (Grant) Wistrom, as far as being ready to play from the start. Trev was a guy that played every single spot on the football field in high school, so he was never able to lock in on any position. You know, a lot of great teams do that, and Trev and Travis were in that same boat. Travis Hill, I remember watching his high school film: he was returning kickoffs, he was playing linebacker one minute, he was playing defensive line the next, he was all over the place, you know?

Both volumes available on Amazon.com

Q: I bet that was interesting… watching some of that film.

TS: We had the benefit of doing that at Nebraska. We had the opportunity to look at them and determine the type of motor they had. And if they could play hard every play in the game, they stood out to me. It was only a matter of teaching them.

Q: Can you define a player who has a ‘good motor’?

TS: One, they had to be playmakers. This is my definition, now. I was looking for playmakers, which means they’ve got to play hard every single play. And then two, did they make plays? Some guys play hard, but when you watch the tape they don’t make plays. And for that position, number three, I want to see how fast they can get to top speed. Is it two steps, one step, three steps? Some guys have a better initial burst from start to top speed, so I was looking for that sudden burst.

Q: How did you differentiate the great motor guy from an average motor guy? Any differences as far as mindset?

TS: Well, they’re typically guys that are very, very intense competitors, and for one reason or another they either don’t want to lose or let people down around them. You’ve got to go have great ability, too, but the ability is not always the most determining factor. You might watch them on film and they might make two phenomenal plays, but then when a play goes away from them they just jog over there. Those are the guys you can develop, but if they already have it in them that they go hard all the time -it could be from great high school coaching, it could be from parents, it could be from a brother when they were young and told they always had to go hard- if it’s already ingrained that’s one less thing you have to worry about.

But you‘ve gotta go back and remember this is not an exact science, so you’ve got to pick a guy to come to your school who pretty much feels they can make it. Because if you pick a guy and spend a whole year developing him and he doesn’t make it competing at the highest level you’ve lost that whole year.

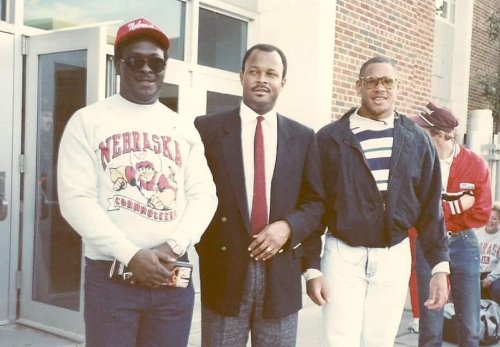

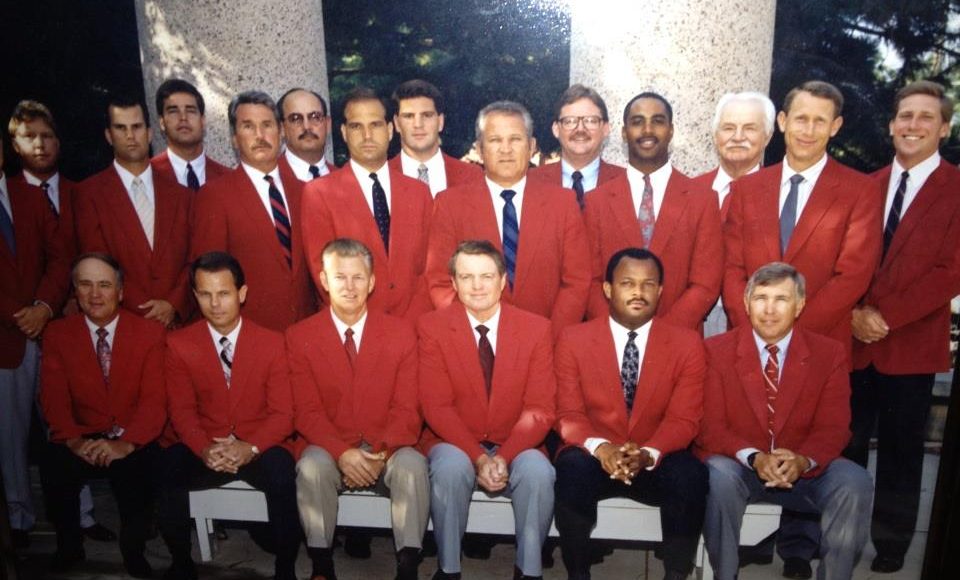

Husker Coaching Staff: Tony Samuel, front row 2nd from right. (Nebr. Sports Info)

Q: Take me into a typical staff meeting…

TS: We started in a full staff meeting -not every day- but for the most part we’d start out with staff meetings. Of course, certain people would come in and give a report: an academic person would come in and give a report, or you might have Boyd or another strength staff member come in and give a report, or the training staff give a report, you always had something going. Most of the meeting time, especially in-season, we’d separate into offense and defense.

Q: Let’s say you’re putting together a game plan vs. Florida State or Miami. Did everybody have input? What was that dynamic?

TS: We really were together for such a long time, and I was a part of that system for so long, Charlie was there before I even left and I was GA for those guys. And, of course, I played for George and all those guys were there, John Melton was there, everybody was there. We all knew each other 100 years, you know what I mean? And everybody would sit down and kind of look at the film and talk over things we wanted to do, and then we’d go out to practice.

Q: Some coaches are notorious as career vagabonds. What kept you guys together in Lincoln for so long?

TS: For me, I was there 11 years. A good part of it was the way the thing was set up, the lifestyle. It was really a great place to live, raise the kids, the public school system was like most private schools around the country, the quality of living was good. And, of course, you look at the program and you hit it on the head, we were all able to be a part of the system for years and there is a loyalty that had built up there that was incredible.

To be continued….

Copyright @ 2013 Thermopylae Press. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credits : Unknown Original Sources/Updates Welcomed

Paul Koch