Anatomy of an Era: Coach Charlie McBride, Part 1

Excerpted from Chapter 72, No Place Like Nebraska: Anatomy of an Era, Vol. 2 by Paul Koch

Inigo Montoya: Who are you?

Man in Black: No one of consequence.

Inigo Montoya: I must know…

Man in Black: Get used to disappointment.

-William Goldman, The Princess Bride

Alexander the Great: World conqueror joining East and West, history’s maverick integrator of infantry, cavalry, engineering, logistics and intelligence support.

Hannibal: Rome’s unrelenting tormentor, forty elephants and 50,000 men traversing the Alps into Italy to vanquish the very City of God itself.

Genghis Kahn: A horse-drawn and extremely agile cavalry possessing leather helmets, breastplates, lances and swords, his ‘mongol hordes’ and their infamous ‘groupings of ten’ inflicted psychological terror to great effect.

Leonidas: Hero-King of Sparta, led the defense of the famed ‘300’ against the vastly outnumbering Xerxes’ Persian armies at the Battle of Thermopylae, a.k.a. The Hot Gates, securing time enough for the Greek states to assemble their own defense for their (and a subsequent world’s) continuance as democratic, free men.

Great leaders, all. Tactical genius. Strategic brilliance. Charismatic personalities. Relentless in warfare. Endeavoring total domination. Dedicated patrons. Protectorate of their fighting men. But who am I forgetting? Oh, yes…

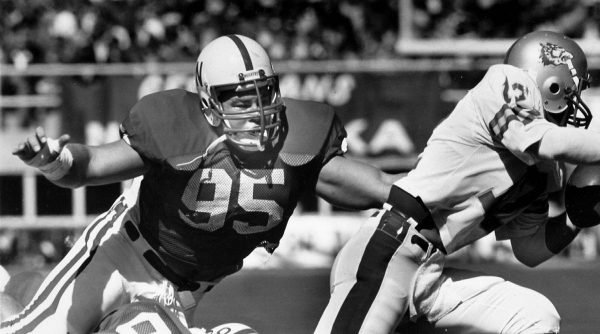

Charles Thomas McBride: Spirited, dauntless leader of the unflinching, feared and revered Nebraska Blackshirt defense, thwarting opposing offenses and inflicting undue misfortune every fall football campaign from 1982 to 1999 on the Western American Plains.

Hyberbole? Maybe. Some semblance of truth? Sure. Providential? Absolutely. History is spotted with rare individuals possessing unmistakable boldness of character, of hair-trigger temperament, of purposeful spirit, of models of manhood in the cruelest of environs, of undying love for annihilitic perfection. Like Hannibal, whom history only knows by his enemies’ oral admirations, Charlie McBride had an unquenchable thirst for tearing down a foe’s best laid offensive game plans. Like Genghis Kahn, his minions dealt macabre blows and left lasting fear, taking no prisoners. Like Alexander, his judgement in soldiers’ capabilities amid battle knew no equal, immune to defeat. And like Leonidas, his troops feared no one in no place at no time. (Call it a Spartan swagger)

Defensive Coordinator and Line Coach Charlie McBride must have descended from such men, placed squarely into history by his Maker at the precise, most desirous of times. Dr. Tom Osborne had a hell of an offense, this is true. But to win championships you need defense. And a stalwart one at that. So much so that Nebraska’s defense became an offense of sorts. Such was the pluck and the spunk of a man and his marauders, his beloved Blackshirt tribe roaming the midways and laying down swift frontier justice on any foe contemplating crossing the goal line.

I had a wonderful, rambling conversation with Charlie one night while we watched a college bowl game on television. The time spent wasn’t necessarily about strategy, about tactics, about opening the doors of the old staff war rooms or the grease boards of a game’s sideline chalk-talk. Instead, it was about getting to know a man for who he is, and was, and how he became the simultaneously feared and beloved leader of the young charges who knew him best. His is a journey of discovery in and of itself, and you can bet Jack the Bear that his Chicago origins played a huge role in the making of the man. I hope this dialogue contributes in some small way to his myth and perhaps even his legend. It would be rightly deserved, if so, for history hasn’t even begun to adequately touch upon the man and his accomplishments at the Cornhusker defensive helm. Let’s listen up as Charlie holds court.

Notable quote #1:

“Sometimes it takes a little tough love, sometimes it takes some patience. A lot of kids are different. Some kids it takes two years to really learn the stuff you’re trying to teach and some kids pick it up in two seconds.”

Charlie McBride

Question: Hey Charlie, I really appreciate your making yourself available for this project I have here. Hopefully there’s something to learn from all those hours and years you put in…

Charlie McBride: Well, okay. My wife figured it out one time and said that I earned a nickel an hour, so that’s pretty good.

Q: (laughs) Now, is it really true that you’d originally began your career as an offensive line coach?

CM: Yeah, when I coached in high school in Chicago for a couple of years. In fact, it was funny, it was a new staff from when I had left there, and one of the coaches came in to recruit one of the kids I had there in the Chicago area. And he looked at me and said, “Are you going to stay here?” I grew up in an inner-city school and this was the school next to the one I was at, and I said, ‘Yeah, I grew up here.’

Later as time went on he asked if I’d be interested in being a graduate assistant, and then I went back to Colorado and did all the way up to my two papers -it was either that or a thesis- and I did the two papers. And then in the middle of that semester I was hired at Arizona State by Frank Kush to coach the offensive line, which I was primarily doing then.

Q: So you went back to your old alma mater: Colorado?

CM: I was primarily an offensive player even though we played two ways. So anyway, I was there three years and then I went to join Paul Roach, who was at Wyoming. (Because we had played against each other) Paul one day called and asked if I was interested in going with him, because he was going to become the offensive coordinator at Wisconsin, and if I would like to be the offensive line coach? Well, I wasn’t really interested in leaving. However, my folks didn’t get to see me play very much in high school or college, especially my dad. My dad only saw me play three or four times, period.

Q: Really? What did your father do for a living?

CM: Well, he worked over in the steel mills. He worked in the forging mills, he sold grinding wheels and stuff. They were over there working with that stuff the whole time for I don’t know how many years. He had that business with his company for about 15 years and he was there a lot. And we played on Fridays, we did not play any night games. So he was working. And then my mom was a volunteer worker, and so she was the only one who got to the games. Well, the point was, I didn’t want to leave Arizona State because I really liked it, but because my dad didn’t get to see me play very much I felt I owed him something. It’s only 130 miles from Chicago and they got to come up there. And my Dad’s story is kind of interesting, because he was Woody Hayes’ roommate for three years at Denison University in Granville, Ohio.

Q: Really?

CM: Yeah, and my dad would never take a promotion, he was such a homebody. So he’d just stay as a salesman. And we stayed two blocks away from where he grew up, and I lived with my grandmother because she was alone. I was the oldest in the family, so I lived with her about three quarters of the time, at night especially, because he didn’t want her staying alone.

So anyway, I grew up across from the city park and started in athletics. I went out for baseball, football, basketball, just kept going year round. I just went across the street and that was it, we all went to the same high school, all went to the same grammar school. It was the typical Chicago Irish Southside neighborhood, you know? (laughs) But anyway, that’s kind of why I went back to Wisconsin.

Q: Wow, so you were a Badger right before joining Nebraska?

CM: And then what happened there, I was the offensive line coach and they fired the defensive coordinator. And we had some real good coaches on defense and the head coach knew I could get people to play. That was his point, and that was one of the things, “the guys on defense now would be able to help you.” Well, now I was gonna coach defensive line instead of offense -so that was nothing- but it was a matter of calling defenses and doing that stuff. And that basically ended up being nothing, too. It wasn’t that hard, but it was a matter of learning the schemes as far as the secondary coverages and things like that. But that year I went and coached the defensive line.

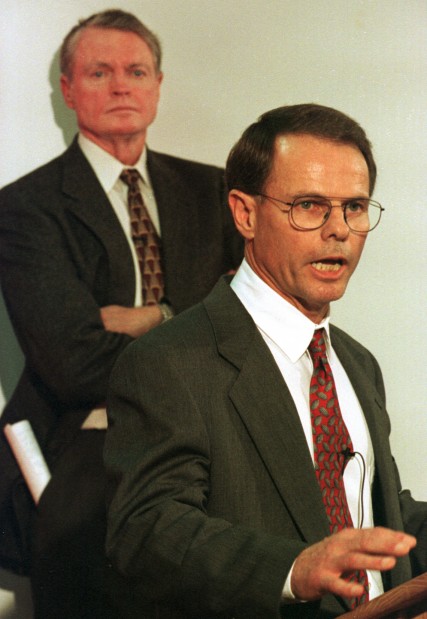

And I guess Coach Osborne found out, somehow. They were looking for a defensive line coach and there I was. That was kind of the point. And then it was one of those things where I was called into the office by the head coach. (I almost thought I was getting fired.) I didn’t think I would be, but when (Tom Osborne) said that he wanted me to be the defensive coordinator I nearly fell out of my chair. (laughs) But I tell you, it’s the best thing that happened to me because I really enjoyed it.

Available on Amazon.com

Q: Did you have a favorite side? Offense or defense?

CM: Actually, coaching the offensive line is boring. You do the same thing every day and every day. Defensively, you’ve got different things happening: You’ve got new schemes, got to get ready to play different things, got different blocking schemes, something new all the time. And I liked that part. I liked practice, teaching.

That was one of the main reasons I really never pushed for a head coaching job anywhere. When I go back and think about it again, I had a ton of chances to go into the NFL and turned them all down. And the last thing I hear, all of a sudden I’m not hearing from anybody anymore, and people said I was just ‘married to Nebraska.’

Q: Who tried to hire you away? Any names?

CM: Tom Landry tried to call, and Tom came in -Osborne- and he said, “Landry is going to call you tonight. He wants to know if you’d be interested in coming down to Dallas to be defensive line coach for the Cowboys.” And that was about the last job offer.

And I went down there. And I don’t know if many people ever told Coach Landry ‘no’. (laughs) My kids… I had a thing where I worked with a couple of guys and they kind of ‘lost’ their kids because they moved. They were in high school and the kids rejected it. In fact, one of them: his daughter doesn’t even talk to him to this day, actually. I think they get a Christmas card. And I didn’t want to be that way.

And then there was Green Bay: I could have gone there with Bart Starr one time, but my kids would have been in three different high schools. And then as a kid you never know where you’re from. ”Where are you from?,” you know?

Q: Kind of like a military brat?

CM: Yeah, and I always wanted my kids to say that they had grown up in Lincoln. And that’s one of the reasons, you know? That’s a pretty strong reason… and the fact that I neglected my children when I was younger. I didn’t realize that I was gone all the time when my kids were really little. I’d come home when they were asleep and leave before they got up. And we played at night at Arizona State, so you never got done until one o’clock at night. And then Sunday you’d get up in the morning and you’d go to work and the kids are just getting up. So you wouldn’t even see them hardly on Saturday or Sunday ’cause you’re locked in a hotel from Friday to the game. So I’d never see the kids on the weekends.

So it got to the point where I was a little older and got to realizing that they’d call on the phone and they’d just ask for Mom, you know? It was like I wasn’t even around. So you finally start to realize all the time you put in. And as they got older it got better, because I saw one of my sons play one game of football or two and I saw one game of my son playing baseball. (All my kids didn’t play football. Both of them played until their sophomore year and then one went with baseball and the other went with basketball and that kind of stuff.) They were just small. They were good kids.

Q: Do your kids live near you these days?

CM: All of them. All three of them live here and all of the grandchildren are here, and two of my wife’s three brothers are here. It’s nice. But with the economy the way it is here, it’s really tough now. And we go back to Michigan in the summer; they’re really in bad shape. My brother was a teacher there for thirty years and we had a place, my dad bought a place and -believe it or not- just about 67 years ago and they paid five hundred dollars for it, it’s on this lake. And the lake’s nine hundred acres; it’s a real nice lake, thirty miles east of South Bend, Indiana, where Notre Dame is right down Interstate 80. And we’re just three miles into Michigan.

Q: Were you much of a fisherman?

CM: When I was a kid I caddied, so I was more of a golfer. And I did fish with one person at the lake, an older guy at the time. I was the only one who could sit in a boat with him for eight hours. I’ve got my grandkids now and they want to go fishing, and they last about 10 minutes. (laughs) Christ!

Q: You were never averse to a challenge, were you Charlie?

CM: No, that’s the whole thing. You’re challenged every day because you’re teaching, and that’s a challenge in itself.

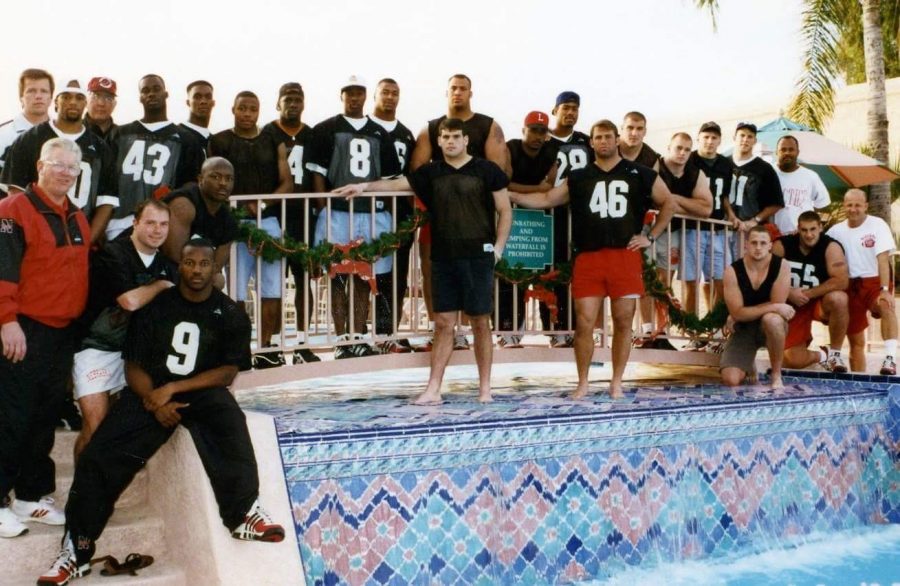

I think the whole thing, when I look back on it? My whole pay was the kids in the locker room when you won. And I have so many different stories of kids that I’ve had. I had one kid who basically brought himself up, one of the first kids I coached at Wisconsin when I was coaching on the offensive line. I had Dennis Lick, who was the fifth player picked in the draft, and then I had Terry Steve and Mike Webster.

And of course, Mike, they said he was too short and he played 18 years in the NFL and is in the Hall of Fame. And Terry Steve was the captain of the Cardinals and played like 10 or 12 years. And Dennis Lick, the first-rounder, he only lasted like five, broke his leg and he was done. But Mike Webster was a special guy. His mom had left, his dad was an alcoholic, his brother was in prison, and he lived way up in Rhinelander, Wisconsin. He was a self-made guy and what a competitor! When I go back and look at the players I’ve had, he’s in that one group where you talk about guys: their motors were running a million miles an hour all the time.

And when you’re coaching and teaching, your whole thing is to make them the best you can make them. And sometimes it takes a little tough love, sometimes it takes some patience. A lot of kids are different. Some kids it takes two years to really learn the stuff you’re trying to teach and some kids pick it up in two seconds. It’s just that way.

Q: Anyone else stick out more than others?

CM: The best technique player I probably ever had was a guy named Rob Stuckey from Lexington. Rob never did play pro ball, and he’s running the Carlisle Group in Washington, D.C., a big kind of a real estate-thing with senators and congressmen. Rob, he was in finance and graduated in three and a half years and actually played his last year as a graduate student.

He was a special guy. His whole family was, really, they were all bankers. His one brother came to Nebraska but then went into finance and transferred to Northwestern. I don’t know if Rob… if he wasn’t playing football he probably would have gone on to Harvard or something like that.

Q: From the start it seems you were around some great coaches. Who had the most profound influence on you?

CM: A guy who had the biggest effect on me was my high school coach, as far as setting a foundation of what kind of person you had to be. And as a player it kind of carried over. He was an old military guy, he taught what they called ‘combatives’ in the Navy, which was basically hand-to-hand combat fighting. We didn’t have weights or spring football, and he was a wrestler -we didn’t have a wrestling team in our school– but we kind of wrestled to get in shape. But there was the discipline part of it and the importance of being in shape and not cheating yourself, and just learning how to push yourself, even off the field.

Q: How would he do that?

CM: He always used to sit me down and ask me how tough I was. And I’ll never forget as long as I live, I didn’t want to say, ‘I’m the toughest,’ you know? Because he may say, “No, you’re not.“ Then you’d really feel bad. (laughs) He said, “You’re not really tough, because you don’t do the things away from football to make you a better person.”

When it got down to it, he basically said, “Toughness is being able to make yourself do things you don’t want to do.” He’d say, for example, “How many times have you gone home at night and knew you had to study, but said, ‘I’ll get up in the morning. I’ll do it in the morning’?” And I said, ‘Well, probably every other night. I’ve done that.’ And he said, ‘That’s because you’re not tough enough to do what you have to do to make yourself better.’

And he said, “I know what you do…,” -because he knew our house- “you set your books on the piano stool, don’t you?” And I said, ‘Yeah, I do.’ And he was tough, you know? Sometimes he’d grab you by the throat -and boy, my dad loved that! Nowadays probably everybody would be, “Oh, don’t touch me. I’ll sue you.”

Q: Exactly…

CM: God, almighty! On no, he would never do anything to hurt you. But if he needed to, he’d get in your shorts good. But I had a little bit of that in me.

And then, I think Frank Kush..

And where I really got my background was from our line coach at Colorado where I played. I was tight end/split end. We did both: if we were in one formation one way we were a tight end and if it went the other way I was a split end. Anyway, Buck Nystrom: about 90% of my offensive line techniques I learned from him.

And when I got out I went and spent a lot of time with Red Miller -who went on to be the coach of the Broncos- I spent time at pro camps trying to learn as much as I could, technique-wise. But my foundation was through my high school coach and Buck Nystrom with my learning, fundamentally, of being an offensive lineman. And when I went to defense it was very easy, because I knew what the offensive linemen were trying to do. And when I’d go to these pro camps you’d pick up what the defensive lineman are trying do just by listening to the offensive line coaches. So actually I felt more confident on the defensive line instead of the offensive line.

And then when I got with John Jardine at Wisconsin -we never had a great team, we were always like 5-5, 6-4, 4-6- we’d beat Nebraska one year and we’d beat Penn State and we’d lose to Northwestern and Indiana- and we never had any depth. As soon as you’d lose two or three guys we were in trouble. And when you’d end up playing Ohio State at the end of the year you were just out of people and stuff like that. But we had some good, really good players. If we put twenty-two guys on the field who were healthy we could beat anybody. But they had never worked out. You’d start losing quarterbacks, and in college that’s like, “Oh boy.” So we spent a lot of time with the running game.

And then, of course, as you go on you learn things from Coach Osborne, some of the intangible things. One of the things was patience. I probably learned that more in my career at Nebraska than anywhere, because we had a walk-on program. And a lot of the kids, you’d think, ‘Gosh, this guy’s not going to play.’ And then as time went on you’d think, ‘This kid’s gonna play some day. He has good work habits.’

To be continued….

Copyright @ 2013 Thermopylae Press. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credits : Unknown Original Sources/Updates Welcomed

Author assumes no responsibility for interviewee errors or misstatements of fact.