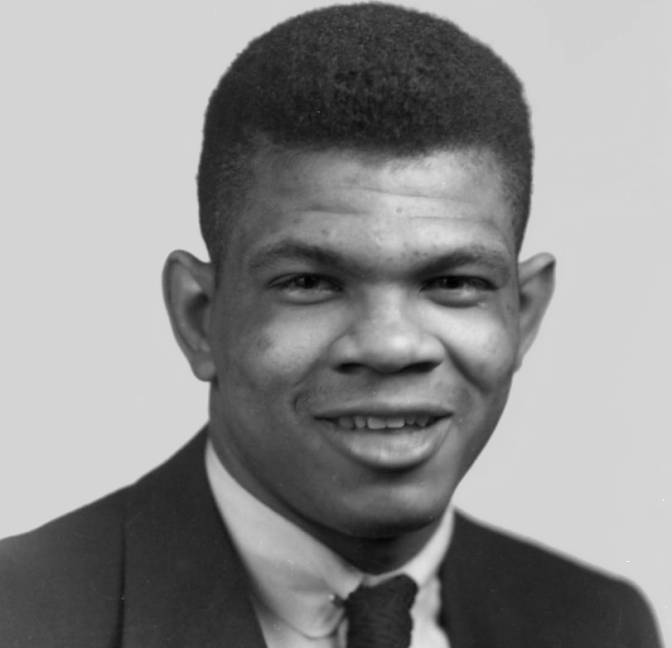

BRYANT

the color line

in the Big 6/7/8

When Charles Bryant walked on in 1951 and became the Huskers’ first black football letterman in four decades, it was one step in the gradual dismantling of the conference’s long-standing color barrier. Read on to see how it all unfolded over a span of more than a decade — and how NU students in 1946 helped bring the issue to the forefront.

Excerpted with the author’s and publisher’s permission from “The Color Line in Midwestern College Sports, 1890-1960,” Indiana Magazine of History, Volume 98, Issue 2, pp 85-112.

By Charles H. Martin

Beginning in the late 1940s, members of the Big Seven conference (later known as the Big Eight) slowly moved to integrate their football and basketball teams. In 1946, following inquiries about the continued exclusion of African Americans in sports, the conference unanimously adopted a policy that was only slightly less restrictive than the previous unwritten understanding. The new regulation stated that “the personnel of visiting squads shall be so selected as to conform with any restrictions imposed upon a host institution” by its regents or state government. This meant that any Big Seven school hosting a conference game had the right to bar black players on the visiting team, if there was a state or university policy against interracial competition. Small wonder then that one observer dismissed the new statement as merely “the gentlemen’s agreement in writing.”30

The decision to adopt a formal exclusion policy upset many students at Nebraska, Kansas, Kansas State, and Iowa State. Student governments at Nebraska and Kansas had previously adopted resolutions endorsing the participation of black athletes in the league. Resistance to the official policy was especially strong on the Nebraska campus. In November 1947, the student council there adopted a resolution urging university officials to work to have the Big Seven repeal its racial ban and to consider withdrawing from the league “if the action is not taken.” The Daily Nebraskan strongly supported the student government’s position and published a poll showing that 58 percent of students questioned favored their school’s dropping out of the conference unless the color line was eliminated. At a late November meeting of student representatives from five league schools in Lincoln, participants adopted a resolution urging the Big Seven to replace its exclusion clause with one which guaranteed that “any eligible student of a member institution shall be allowed to participate in all competitive athletic events at any member institution.” In a surprise move, the student government at the University of Missouri endorsed the meeting’s resolution. The following month, the athletic board of the University of Nebraska formally called upon the conference to delete the controversial clause. But at the end of 1947 the council of Big Seven faculty representatives tabled the Nebraska request.31

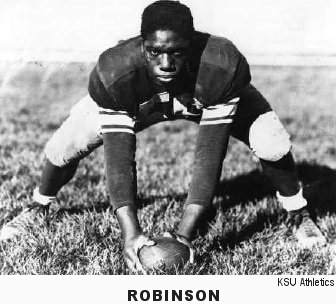

Kansas State then took the lead in challenging the Big Eight’s color line. During the summer of 1948, the football coaching staff urged local star Harold Robinson of Manhattan High School to join the university team. Despite not receiving a scholarship, Robinson nonetheless enrolled at the university and started on the freshman team, paying for his expenses by washing dishes and mopping floors. After a coaching change at the end of the season, new head coach Ralph Graham decided to grant Robinson a scholarship. Graham then sent a letter to the next Big Seven meeting, boldly announcing his intention to use Robinson during the fall season of 1949. “Since there is no ruling against the use of Negro players,” he explained, “we plan to use Harold except at universities where there is a definite rule that decrees otherwise.” When the league did not respond, Graham continued with his plans, and Robinson started at the center position during his sophomore and junior seasons. During these two years he experienced rough play and racial taunts in several games, and on trips to Oklahoma and Missouri he was forced to stay in separate lodging from his teammates. Just before the start of his senior season in 1951, Robinson was drafted into military service and left school. That fall sophomore Veryl Switzer, an outstanding player from Nicodemus, an all-black Kansas town, became the second African American to compete for the Wildcats. Since both young men had been high school stars inside the state, Kansas whites were probably more willing to accept their presence than that of outsiders.32

At the University of Kansas, many students supported the recruitment of African Americans, but university coaches were slower to act than their counterparts at Kansas State. After World War II, black and liberal white students at the university established a local civil rights movement, which challenged discrimination in housing, movie theaters, restaurants, and eventually athletics. Perhaps influenced by this campus activism, Kansas Chancellor Deane W. Malott decided in May 1947 to drop the school’s Jim Crow policy for sports. Malott announced that “any regularly enrolled student at KU may try out for intercollegiate athletics,” provided he met conference eligibility requirements. But Phog Allen, the highly successful basketball coach of the Jayhawks, publicly denied that there had been any change in policy for his teams and instead recommended that African Americans participate in track and field, because that sport “didn’t require as much body contact as basketball.” Despite the liberal student atmosphere in Lawrence and the support of administrators, neither the football nor the basketball program at KU successfully recruited black players for their varsity teams until the mid-1950s. Several other Big Eight members also were slow to desegregate their football and basketball teams. A key breakthrough came in 1956 when Coach Charles “Bud” Wilkinson of Oklahoma University awarded a football scholarship to freshman Prentice Gautt only one year after the school admitted its first black undergraduates. By 1960, every conference school had fielded integrated teams, finally ending the era of segregation in the Big Eight.33

30 Technically the 1946 rule did not prohibit a Big Eight school from including an African American on its team and using the player in games against nonconference foes or an agreeable league rival. However, these limitations made it impractical to recruit black athletes. “Minutes of the Meeting of the Faculty Representatives of the M.V.I.A.A., May 17 and 18, 1946,” typescript, courtesy of Prentice Gautt, Kansas City, Mo., 2-3; New York Times, May 19, 1946; Griffin, University of Kansas, 661, 767.

31 New York Times, April 18,1946, November 20, 23, 30, December 11, 14, 1947; R. McLaran Sawyer, Centennial History of the University of Nebraska (Lincoln, Nebr., 1973), II, 48, 150.

32 During the 1949 season the Kansas State coaching staff left Robinson behind for a road game at Memphis State, because they feared he might be in danger if they directly challenged exclusion in a southern city. Kansas Industrialist, September 22, 1949; Manhattan [Kans.] Mercury, November 20, 1991; Kansas State University Wildcat Weekly, February 18, 1995; Tim Fitzgerald, Kansas State Wildcat Handbook (Wichita, Kans., 1996), 54-57; and miscellaneous clippings, University Archives (Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kans.)

33 One critic of Phog Allen sarcastically commented that the veteran coach “would rather lose every game on the schedule than allow a Negro to play on his team.” New York Times, March 30, 1947; Kristine M. McCusker, “‘The Forgotten Years’ of America’s Civil Rights Movement: The University of Kansas, 1939-1961”" (Master’s thesis, University of Kansas, 1987), 101-102, 107-10; Mike Fisher, Deaner: Fifty Years of University of Kansas Athletics (Kansas City, Mo., 1986), 204-206, 269-71; Diane Boucher Ayotte, Columbia, Mo., to author, August 18, 1994.

HuskerMax thanks Dr. Martin and Indiana Magazine of History for allowing us to provide this insightful information, and we encourage you to read the award-winning full article.

Below is a HuskerMax compilation of links to newspaper accounts of the events of 1946 and 1947, in which Nebraska students’ concerns were largely dismissed by the conference:

Spring of 1946: Student councils at Nebraska and Kansas raise objections to the Big Six “gentlemen’s agreement,” to little avail: 1, 2, 3

Nov. 19, 1947: Nebraska’s Student Council asks for the university’s withdrawal from the Big Six unless the conference eliminates the color line in athletics: Story top | Full article

Nov. 23, 1947: Poll of Nebraska students finds support for Student Council's position

Nov. 30, 1947: Student representatives from conference schools unanimously pass a resolution to eliminate racial discrimination in athletics: 1, 2

Dec 10, 1947: The NU Athletic Board joins the effort: 1, 2

Dec 13, 1947: The conference says no: 1, 2

More about Charles Bryant:

Video feature | Grandson’s story: 1, 2 | OWH bio | 1953 photo | 2004 obituary